Romare Bearden was one of those people who seemed to have known everyone (Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Paul Robeson, Eleanor Roosevelt, Baziotes, Miro, Lorca, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Brancusi, Jacob Lawrence, Hannah Arendt, and Heinrich Blucher) and done everything (he played baseball in the Negro League, pitched against Satchel Paige, studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, was a caseworker for New York City’s gypsies, and composed the dance piece Seabreeze). George Grosz was his instructor at the Art Students League. Stuart Davis and Carl Holty were early mentors. In his art he referenced the Bible, Homer, Delacroix, Lucas Cranach, Byzantine mosaics, Rabelais, New Orleans Jazz, Billie Holliday, Chinese landscapes, Benin masks, the “prevalence of ritual” in the African American South, and the shattering of that ritual in the black Diaspora to northern cities. To paraphrase another reviewer: ‘In those days, a black artist had to know his shit.’ Over the years, Bearden became a virtuosic colorist (think of the luminosity Hans Hoffman achieved but with much, much thinner layering–he often used gouache or watercolor) and master of the picture plane, grounding flat surface with control learned from work of Vermeer, Jan Steen, and Mondrian. Starting in 1961, he began to incorporate collage (and eventually photomontage) into his work. The new medium allowed him to pull together the strands of a rich and painful, intimate and historical narrative. As his friend Ralph Ellison wrote, “His combination of technique is itself eloquent of the sharp breaks, leaps in consciousness, distortions, paradoxes, reversals, telescoping of time and surreal blending of styles, values, hopes, and dreams which characterize much of Negro American history.”

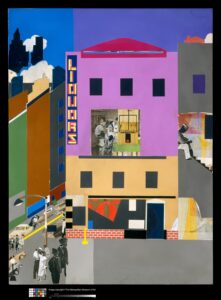

Bearden’s 1971 collage, The Block, is on view at the Met until March 4, part of the tri-state celebration of the artist’s centenary. The piece as a whole is large but not enormous, 48 by 216 inches. It’s meant to be viewed as a single, mural-like composition, but it’s hung as six separated panels. Some early art critics thought it too literal and there’s a temptation to feel that way again, especially since portions—the silhouette of a desolate man with a brimmed hat; an Ethiopian angel receiving a woman who’s just died; a somber-faced couple viewed from behind a half-pulled window shade—have become icons of American visual culture. There’s a temptation to say, “I know what this looks like.” But, take the time to look, and the tableau becomes pretty exhausting—exhausting, in fact, the way it’s exhausting to look at Desmoiselles or Guernica.

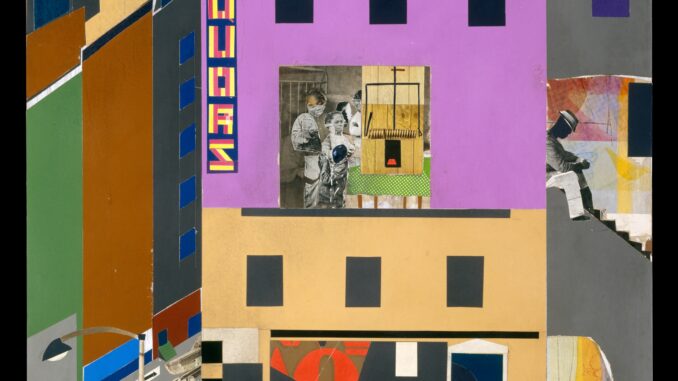

Bearden famously explained his process: “I really think the art of painting is the art of putting something over something else.” That’s essentially what he did, starting with a series of buildings observed from his friend Al Murray’s apartment in Harlem (his rough sketches of the stretch between 132nd Street and 133rd Street are included in the Met exhibit). The building facades provide color blocks and Bearden warmed the urban palette–its gray, clay, and brick-red–with bands of lush colors from the rural South–violet, orange, chalky green, and blue. He thought of the vertical rectangles of his colored buildings to musical intervals but his rectangles are broken apart when he opens up windows and walls to show the lives lived inside (including mousetrap, tables, light bulb, quilt and beds for dreaming and making love). Sometimes using paint, sometimes creating a mosaic of photographic pieces and scissored shapes—hair might be cut roughly from one magazine photograph, eyes from a second, the lower face from a third—he built his figures to become projections from contemporary life, history, memory, and imagination.

Bearden was a beloved personality. A well-known photograph taken in the 1970s show him as roundly heavy, fair-skinned (more than one reviewer compared his appearance to Nikita Khrushchev), half-smiling, wearing a knit hat, holding a cat. Among other things, he helped establish the Studio Museum of Harlem. To honor his centenary the Studio Museum and the Bearden Foundation organized the Bearden Project–lectures, performances, and a year-long show on their premises. Some of Bearden’s work is on view–Conjur Woman, The Farmer, Two Women, and five screen prints entitled Prevalence of Ritual. In the spirit of a birthday party, SMH invited a hundred artists (including some who come close to being from Bearden’s generation: David C. Driskell, and John Outterbridge) to create work “inspired, influenced, or informed” by Bearden’s “life, work and legacy.” Art has rotated in and out during the year and some will remain on view until September 2, 2012.

Much of the work riffs on Bearden’s biography and references his collages in particular. Some of it focuses on the centennial occasion. Marren and Ava Hassinger built a tower of boxes (like wrapped birthday presents– one of them covered with pages from the Invisible Man) up to the ceiling and scattered seashells (a reference to his life in St. Martin) on the ground surrounding it. Simone Leigh’s Blush (for Romare Bearden) is a polished and lyrical, Brancusi-like, form, covered mostly with ivory-colored ceramic roses, though pink, black, gray, brown, gold, and red roses are scattered in. One can read the work as a celebratory bouquet or a lovely dreaming head with curls. Charles Gaines (String Theory) enlarged a printed passage of Bearden’s reminiscence from childhood: When I was a little boy attending P.S. 5 at 140th St., and Edgecomb Ave., there was an annual hegira to the Metropolitan Museum of Art… Then he partially covered the words with graphite shadows, clouds or smoke, reminding us of the mystery of meaning and random ways in which it visits us.

To my mind, two pieces stand out: a dynamic and technically meticulous collage, Efulefu: The Lost One, by a current HSM arts intern, Njideka Akunyili and Kamau Amu Patton’s stunning homage, Untitled, a large, black on black painting on paper—pasted, scratched, scribbled upon, and patched together. It is a deeply synthetic work, brooding, contemplative, and original.

Leave a Reply