Review

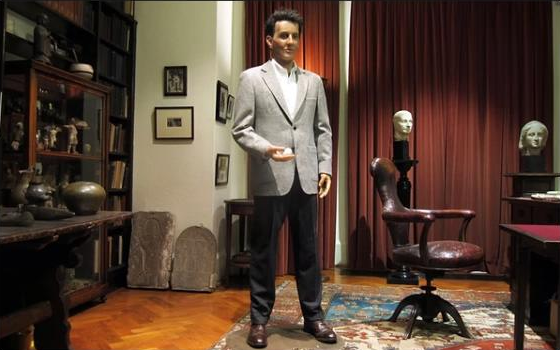

Wittgenstein is not easily dismissible and is said to be the philosopher of artists and poets. However it was my impression that his presence was evoked here much more as a student of Bertrand Russell, as a proponent of logic and as an influence on analytical philosophy through his insistence on empirical evidence as opposed to metaphysics, you know the interesting stuff about freedom and truth. What Wittgenstein would make of his rather suspect likeness contemplating an egg in Freud’s old front room is anybody’s guess; it’s almost as if his entire body of thought is reduced to a footnote in the criticism of Freud’s ideas, and it’s strange to think that Turk drawing on Wittgenstein and arresting him in wax may be doing more damage to him than to Freud.

image © the artist

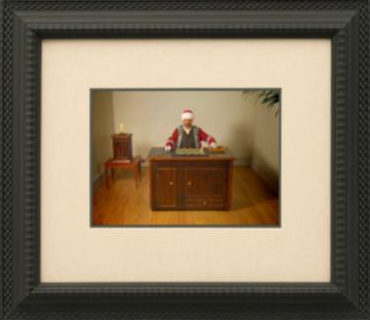

The egg is in part meant to reference such objects in surrealist painting and so we begin with the inverted commas and witty titles that characterise much of the output of a generation that took Duchamp too seriously, in fact most of what’s on display could be said to be titles with titles (not even Hirst has cottoned on to that one). Most obviously in this vein are the neon signs which state; Super Ego, Ego, Id, for example Id is titled ‘that’ and Ego is titled ‘I’.

That, 2015

The experience of seeing neon in an early 20th century period interior is novel but the idea spelled out by the images, literally, is rather thin and for all its manufactured sophistication puts me in mind of a foundation arts student grappling with concepts cut and pasted into their practice from Wikipedia.

This is a tendency common to many old YBAs I can almost hear Tracy Emin bemoaning the intrusion on her territory (neon) and wishing she had the originality to commission the glass and light specialists to fabricate her next masterpiece.

These works return me to the pictorial title of this review employed in a number of comedy panels. The visual pun is not too harsh a summing up what this work offers. It reads like an essay, there is only what is being said or explained by the artist who tells us that ID has the quality of ‘that’ a certain thing-like status, ok, yes and we move on. The images of plumes of smoke also make rather obvious points; 1 Freud smoked cigars. 2 Pareidolia is making things out of patterns or natural phenomena like clouds or smoke. 3 Parapraxis (the title) is a slip of the tongue which reveals the truth. Here Turk is wondering if the associations and projections we make are really meaningful (Freud) or just chance and arbitrary (Wittgenstein) but of course Turk is unpacking Wittgenstein’s argument in his title ‘Parapraxis’ that the significance of these phenomena is a Freudian slip, literally it’s all Freud’s mistake.

This is reinforced by the ‘Mechanical Turk’ video work which quotes the famous con in which a supposed automaton beat chess masters at their own game. What was actually happening was a little chess master hiding in the bowels of the machine was actually operating the controls and playing people; audiences were amazed that a machine could achieve such a thing. So we have Turks within Turks or perhaps nobody’s home.

Mechanical Turk 2015

I must admit I did pause here considering the historic associations and thinking of the character Rachel from the film ‘Blade Runner’ with her existential angst about having fake memories and not being real, by way of ‘uncanny valley’ we may yet have Rachel’s worrying away at these dark insights. I began in spite of myself to warm to Turk’s intervention, there is even a famous image of Rachel smoking which brought back the images of the plumes of smoke from ‘Parapraxis’ however what made Rachel an intriguing character and for that matter what worked about Blade Runner was its ambiguity and the projectability of its themes and characters, it demanded interpretation not reading this allows Rachel to live in the imagination forever questioning her humanity, will she live, is Dekkard real and so on.

This ambiguity is present in great artworks – the best of Max Ernst or Giorgio de Chirico to follow the surrealist examples – and is meant to activate the psychic transformation that Breton was interested in. I suppose its ultimately this Turk doesn’t supply enough of, his statements are just that, they don’t open a space for my thoughts but rather attempt to subtly weaken my resolve and fill me with Turk’s thoughts. There is something despite the ironic winks and in-jokey-ness of the old YBA that is rather too empirical to be that generous, his weight (Turk’s) seems to me to be behind Wittgenstein and the facts even if that means human personality and agency are a mistake given credence by the theories of Freud.

Alain Badiou said at a conference in Birkbeck that, ‘Truth is not made of facts it is the becoming of the subject’. In an interview I conducted with Malcolm Quinn he stated that in, ‘Psychoanalysis truth emerges as cause,’ in this way improvement, transformation and change is the only credible action and for this we need space the kind held open by a pseudo-science never totally at peace with the empirical facts.

Regarding Turk remember that he is confident enough to place himself between two huge minds of the 20th century and I’m sure robust enough to withstand being taken seriously and criticised in the name of the rehabilitation of actual criticism rather than the glib celebration or outright shameless advertising, or worse still the perfunctory automatic mechanical print that is churned out between coffee break and lunchtime by the supposed custodians of our public taste.

My final thought upon leaving the museum is if Turk imagines Wittgenstein putting psychoanalysis in its place with dry logic and a dash of Turk brand irony then I imagine Roy Batty (the angry superman in Blade Runner) crushing Turk’s wax head to remind him of the seriousness of the stakes. Remember Gavin, ‘when you’re dead, you’re dead’.

‘Wittgenstein’s Dream’ Freud Museum, 26 November 2015 – 7 February 2016

by Michael Eden

Images © the artist

Leave a Reply