As Shakespeare pointed out, men were deceivers ever. Maybe he’d met Lucas Cranach (the elder model), as back in 1509 the German was busy falsifying dates on his prints to try and prove that he had invented a new art-form. The man he was trying to prove had copied him was Hans Burgkmair (the Elder) and what one of them had invented was chiaroscuro woodcut printing. Scholars believe that Hans got there first, in which case his 1508 print of Emperor Maximilian on Horseback is the first chiaroscuro woodcut print ever made.

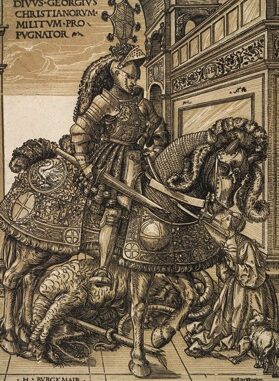

Here’s one he did later… Hans Burgkmair the Elder c. 1508-10 Collection Georg Baselitz Photo Albertina, Vienna

Meaning light-dark in Italian, chiaroscuro already existed as a technique for modelling shadow in painting and drawing. But it had never been attempted in printmaking before. As I write that I realise it sounds a very niche interest. Chiaroscuro had never been attempted in printmaking before you say, how interesting. I can imagine you looking over my shoulder for someone else to talk to. Don’t worry, if we met at a party I wouldn’t launch straight in to the delights of chiaroscuro woodcuts, there are plenty of other subjects on which I can Bore for Britain. If though you are thinking hang on, chiaroscuro printmaking, that sounds interesting then I have an address for you to visit. There’s a great exhibition of Chiaroscuro woodcuts at 44 Piccadilly until 8th June. It’s probably better known as the Royal Academy.

The show has travelled from the Albertina Museum in Vienna (a museum on whose website your cursor will currently turn into Durer’s hare…). It comprises over 150 works from both that museum and avid chiaroscuro print collector and honorary Royal Academician Georg Baselitz. Some of the earliest prints in this style are on display, showing a formal, stiff drawing with the emphasis on line, including both images that are pretenders to the disputed First chiaroscuro woodcut ever crown.

Of course printmaking already existed before 1508, but it only created images with single colour lines. The new technique used several woodblocks to create one image, by printing them in turn on top of each other. Each is cut differently and inked with different colours. They each add a different tone to the image and enable the modelling of light and shade to be achieved in a way previously impossible. It was not an easy procedure, as a video in the exhibition shows, and many of the early artists employed wood-cutters to make their blocks. The show provides a complete account of the birth and development of this new technique and demonstrates that it was soon taken up by two artists in Durer’s circle, Baldung Grien and Hans Wechtlin, along with masters such as Albrecht Altdorfer – although Durer himself though did not take up the new method of working.

‘Prints were the internet of the 16th century,’ claims Dr Achim Gnann of the Albetina Museum . That’s quite a bold claim, and I don’t think Sir Tim Berners-Lee would agree that he had merely re-invented print-making. But prints were used then in a similar way to the internet nowadays – to disseminate information and images. Prints were how artistic developments in Germany were conveyed to Northern Italy. It might have taken a month for the information to trickle across the Alps, but this was how an artist like Ugo da Carpi in Venice would have come across the technique. He not only came across the technique, he started practising it himself. As the only other practitioners were several hundred miles away and only spoke German, he went a step further and claimed to have invented it. He even went several steps further than that by applying for a Venetian patent to stop anyone else using his technique in the area. A bold fellow was Ugo da Carpi.

His claims of having invented chiaroscuro woodcutting were balderdash, but he did develop the technique, leaving behind the emphasis on line and working more intently with tone blocks, giving a painterly impression to his works which can be seen in his masterpiece Diogenes in the show. His follower Antonio da Trento pushed further in this direction, working from preliminary drawings by Parmigianino whilst developing a more fluid, rhythmic style. Niccolo Vicentino also worked from Parmigianino’s drawings, copying Da Carpi’s style so precisely that his work is often hard to distinguish from the Italian ‘inventor’ of the technique.

In the later 16th century Andrea Andreani pushes the technique to the limits of size, whilst Dutchman Hendrik Goltzius shows some of the sophisticated effects that could be achieved by a master. With many works and artists to discover this is an exhibition that might lack blockbuster appeal but brings attention to a little known art form. Even if no one is quite certain who invented it.

Leave a Reply