The Bechdel Test was created as a joke by Allison Bechdel in a 1985 strip of her comic ‘Dykes to Watch Out For’. However, it has since been taken seriously as it highlights an ongoing problem in the entertainment industry, that being the repeated lack of substantial female roles which are significant to the plot of a film. This then indicates an institutional pattern of marginalisation of women. It is not an indicator of ‘feminism’, simply female presence.

The Bechdel Test is simple:

- There have to be two or more named female characters,

- Who communicate with each other,

- About something other than a man.

Pop culture media critic Anita Sarkeesian uses the Bechdel Test in her recent videoblog for Feminist Frequency to assessthe current batch of Oscar nominations. Watching this straightforward and comprehensive analysis prompted me to apply the Bechdel Test to other areas of the entertainment industry, mostly current TV series, and I, like Sarkeesian, struggled to find positive results.

The 2012 Oscars and the Bechdel Test – Anita Sarkeesian for Feminist Frequency

The Bechdel Test is the absolute lowest we can set the bar to assess women’s meaningful presence in a film. Sarkeesian argues for an addendum to be made to it in that the communication between women must last for longer than 60 seconds. This is in an effort to pass films on the basis on meaningful and significant female interaction, rather than a brief one-liner of no consequence. It upset me that she felt the need to put this addendum forward so formally, as a halt to the massive volume of calls to pass a film based on the most minute as negligible of female to female dialogue, and I fully agree with her that if a film needs to rest its entire argument for inclusion of a positive female role based on a few brief unimportant seconds, then it is implicitly indicative of a problem with women’s representation.

Although the Bechdel Test doesn’t look like a lot to ask, it is shocking how low the pass rate is.

Sarkeesian examines the nine nominations for the 2011 Oscars, as these films are generally considered to be the ‘best of the best’ by the academy. Through her direct summaries, a trend of male-centric films emerges:

The Descendents – personal growth story of the father figure.

While Sarkeesian shows that this film does pass the Bechdel test though a few brief interactions between the daughters (although not with the 60 second addendum), she highlighted a point that I have previously struggled with: it is a father’s personal journey that we (the audience) are interested in, with the mother character being killed off early on to provide the catalyst.

Although I enjoyed The Pursuit of Happyness (2006), I have been repeatedly irritated that it is a story exploring a single-father’s difficulties, to the neglect of addressing that single-mothers face the same problems. Chris Gardner fights to hold down a regular job, fails to find appropriate and affordable childcare, is evicted with his small son for failure to pay rent and struggles to retrain and develop a career which will both provide for his son and personally fulfill him. As far as I am aware, no such film has been made depicting how single-mothers handle the same difficulties, which I find peculiar given that single-mothers are more common. It most certainly didn’t reach the same dizzying heights of fame as The Pursuit of Happyness. Also, there are many female-centric, real-life, single-parent success stories which would make excellent biopics (JK Rowling, Coretta Scott King, Lauryn Hill, etc).

This is not to demean the achievements of Chris Gardner, but rather to highlight an inconsistency in Hollywood: if a feel-good film about the success and personal growth of a single parent is such a good formulae, then why aren’t there any/many about single-mothers?

Using Wikipedia’s List of Biographical Films for the 2010s, there are 23 out of the full 76 which have a central female character, a total of 30%. However, many of these women are featured in conjunction with a central male character (Winnie Mandela, Eva Peron, Marilyn Monroe, Catherine Middleton, etc), including the only one to reach high critical acclaim (Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in The King’s Speech), which itself only passes the Bechdel Test by the narrowest of margins. Why must these women be depicted in reference to a man? Or, in cases of Mandela, Middleton and Bowes-Lyon, they are only a central character due to their relationship with a man, and not on their own individual merit. There are several excellent biopics which do focus on the woman as an independent and autonomous being (The Iron Lady, The Danish Girl, The Runaways, etc) but not enough to balance the overwhelming majority of male-centered and male-dominated films.

Moneyball – biographical sports drama story.

Fails the Bechdel Test, but it is still a good film.

The point that Sarkeesian makes about this film is that while it is a male-centric story, it could only ever be a male-centric story and it makes sense that there aren’t any meaningful female characters. The importance of this point is that films like Moneyball make up the vast majority of Hollywood’s output: this is not a one-off male-centric story. For every male-oriented biopic, there isn’t an equivalent female-oriented one. Even films which could have half of the characters as female chose instead to make them male (see other 2011 Oscar nominees of Hugo (orphan boy investigating his father), Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (boy losing his father) and War Horse (boy and his horse)). Even Midnight in Paris (man struggling to discover himself), which features anti-patriarchy campaigner and lesbian Gertrude Stein, fails to pass the Bechdel Test, such is, as Sarkeesian asserts, the arrogance of Woody Allen that he refuses to allow Gertrude Stein to speak with another women.

Tree of Life –about a boy and his family.

While it this film does not contain much dialogue, it still manages to include several long interactions between father and sons, and does not pass the Bechdel Test. This film raises similar questions as above, in that the father/son relationship is widespread across Hollywood, whereas the mother/daughter, or even father/daughter and mother/son, relationships are ignored, or are, at least, not the main focus and drive of a film.

Unlike Moneyball, however, this film is pure fiction and not based on a biography. This then raises the question as to why the parent of focus and all the children are male? Would the audience have cared as much if it was a coming-of-age story about a girl, or the troubled relationship between a mother and daughter? Would it have been deemed worthy of an Oscar? Sarkeesian’s brief discussion on this particular film reminded me of another personal irritation of mine concerning the immense popularity of the Harry Potter books: would they have even been half as successful if they had been the Harriet Potter books? There isn’t much in the plot that would suffer if the genders of all the characters were inverted, so why have a hero and not a heroine, and why have most of the tension, especially in the later books, focus on Harry’s interest in his father, not his mother?

The answer is simple: boys are not (on the whole) interested in stories about girls, whereas girls will read about boys. This is a phenomenon that’s been around since children’s fiction really took off in the 1940s, with Adventure Books for Boys being eagerly consumed by the sisters of their intended audience, but the properly feminine tales of domestic chores and motherly-make-believe with dolls being shunned by boys (and many girls). Here we are getting close to the nature/nurture argument in discussing whether little boys really aren’t interested in homemaking, or if they have simply been repeatedly told that they are not. Thinking about it closely, while the Harry Potter books (and films) do pass the Bechdel Test, it is not by much, as direct conversations between the main female characters are usually inferred to off-page or off-screen and the reader/viewer rarely witnesses them. The few that do occur on-page or on-screen are in the presence of a male character, with that male character also interacting.

We can see it in film consumption as well, with specifically female oriented films being repeatedly derisively dismissed by critics and many male-audience members as ‘chick flicks’, whereas many male-centric films have sizeable female fan bases (I, personally, cannot get enough of Die Hard). Here we see a worrying tendency of female-centric films being dismissed for being female-centric rather than on the basis of any sort of critical merit. Until this is challenged, script writers will continue to make their central characters male, for both critical and financial gain.

One film that did challenge this recently was the critically acclaimed and commercially successful Bridesmaids, which Sarkeesian picks up with relish. Here we have a film that depicts women and women’s relationships with each other in a genuine and meaningful way, and was taken seriously by both critics and the viewing audience of both genders. It is a refreshing change to an otherwise male-dominated industry, and will hopefully be the encouragement and validation writers, directors and producers need to vary their output slightly.

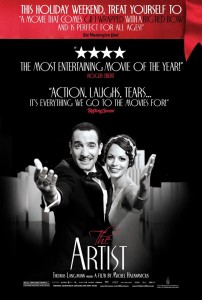

The Artist fails the Bechdel Test as the two named female characters (Peppy Miller and Doris Valentin) do not even meet.

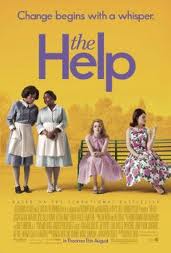

So, out of all nine Oscar nominees for 2011, we are left with The Help, which passes the Bechdel test with flying colours! Hooray! This is a woman-centered story with a varied female cast. However, when Sarkeesian applies a variation of Bechdal Test to ascertain positive and meaningful interactions by people of colour, it fails miserably. This film is about racial inequality and marginalization, yet it marginalizes its black characters by having all dialogue either consist solely of, include, or be about, white people. Thus, while it is a welcome relief from the repetitive male-centric plots of the vast majority of Hollywood outpourings, it remains exemplar of the assertion that Hollywood does not make films for a general audience.

Off the back of Sarkeesian’s discussion, I found myself applying the Bechdel Test to current television programming. Using my own UK TV guide, it is shocking how few there are that feature a women not discussing men. ITV’s Loose Women comes to mind.

This is a 4-women panel show with occasional guests, and while these women do frequently discuss men, their conversation also thrives on non-male-oriented topics. However, the programme tends to be seen as somewhat of a joke, choice comments being that it is “flumpf telly” which “you don’t have to think about” (Karl Pilkington). Daily Mail columnist Jan Moir slated it for being “a gaggle of sexual incontinents” after the show won a 2010 National Television Award, and it was criticised on by The Guardian as offensive and having a politically incorrect representation of an all-female cast of panelists (6th June 2008), a peculiar criticism to level at this show and not male-dominated panel shows, such as…well…every single other panel show on TV. From Top Gear to QI, the majority of panelists and guests are male, and when there is a female comic, celebrity or guest, she is alone with the men, so the very first requirement of the Bechdel Test is failed.

This is a 4-women panel show with occasional guests, and while these women do frequently discuss men, their conversation also thrives on non-male-oriented topics. However, the programme tends to be seen as somewhat of a joke, choice comments being that it is “flumpf telly” which “you don’t have to think about” (Karl Pilkington). Daily Mail columnist Jan Moir slated it for being “a gaggle of sexual incontinents” after the show won a 2010 National Television Award, and it was criticised on by The Guardian as offensive and having a politically incorrect representation of an all-female cast of panelists (6th June 2008), a peculiar criticism to level at this show and not male-dominated panel shows, such as…well…every single other panel show on TV. From Top Gear to QI, the majority of panelists and guests are male, and when there is a female comic, celebrity or guest, she is alone with the men, so the very first requirement of the Bechdel Test is failed.

This extends to reality TV shows, such as the X-Factor and Britain’s Got Talent. While there are both female and male judges, the nature of the show means that the women do not interact with each other without the male judges also being a part of the conversation. There are occasional conversations between female mentor and female contestant broadcast, but, again, it is in the minority. Also, the female judges are very rarely as professionally successful as their main counterparts: Danii Minogue, Cheryl Cole, Kelly Rowland, Tulisa, Alisha Dixon, Sharon Osbourne et al. cannot claim the same levels of success, professional standing and respect or, indeed, power and influence, as Gary Barlow, David Hasselhoff, Louis Walsh, Piers Morgan and, of course, Simon Cowell. It definitely gives me the impression that women do not have to be as professionally successful as men, as long as they’re pretty. The women are also the most replaceable, with each new series tending to retain the male judges, but bringing in a new female face.

The easy counter-argument to this is that it is representative of the real world: there are fewer female comedians, politicians, general public figures, so their representation on TV panel shows is accurate. But what about fictitious drama? Women are half of the population, so surely half of the characters in shows should be female, and should be able to hold conversations with each other that do not focus on a man, like most women do every single day. But we are again sorely disappointed.

Using results from the Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board for the top rated programmes on the UK’s most popular freeview channels of the week ending 12th February 2012, and applying the Bechdel Test, the findings are:

- Call the Midwife – BBC1 – PASS

- Top Gear – BBC2 – FAIL

- Junior Doctors – BBC3 – MAYBE

- The Natural World – BBC4 – FAIL

- Coronation Street – ITV1 – MAYBE

- One Born Every Minute – Channel 4 – PASS

- Come Dine With Me – More4 – FAIL

- Desperate Housewives – E4 – FAIL

- Star Trek – Film 4 – FAIL

- NCIS – Channel 5 – FAIL

- Suits – Dave – FAIL

Out of eleven shows, only two pass the Bechdel Test, while a further two have grounds as possibilities. The Natural World can be discounted as human interactions were not its focus. So, even in the most positive interpretation, meaningful female representation still consists of less than half of TV programming (40%). It is interesting to note that the two programmes which do pass the Bechdel Test are both midwifery shows.

Desperate Housewives had great promise with a strong female ensemble cast, and there have been many episodes across its eight series which have passed the Bechdel Test. But the driving tension in the current series is the murder and collective cover-up of Gabby’s stepfather, which has unfortunately resulted in most of the interactions between the four main women being focused on this particular man. Indeed, it appears to me that these four (five with the inclusion of Vanessa William’s Renee) have been reduced to simplistic two-dimensions whose lives revolve around the whims and actions of various men: Lynette is struggling with her divorce, Gabby is struggling with her husband’s guilt over the murder, Susan is struggling with her demanding (male) art teacher, Renee is struggling to win over new guy Ben, and Bree (formerly the strongest and most independent character) is struggling with creepily possessive ex-boyfriend cop Chuck and has had to throw herself on the mercy of Ben to protect her. None have independent careers, none meaningfully interact with women outside of this small core group, and now they only talk to each other about their menfolk or the murder.

Call the Midwife is a dramatisation based on the memoirs of Jennifer Worth, a midwife in the East End of London in the 1950s. The cast is predominantly female and the conversation and drama revolves around their female patients and personal relationships with each other as friends and colleagues. Yes, there are a few storylines on romantic relationships, and the husbands of the pregnant patients are featured well, and this is right because it is accurate. But it is not the sole focus of the series. More importantly, it has been remarkably well received and draws mixed audiences of both genders regularly. This programme, alongside Channel 4’s docu-drama One Born Every Minute, following midwives in NHS hospitals, show multiple women in meaningful roles and participating in relevant interactions. I find it a shame, though, that this is currently being achieved through the same medium, midwifery, rather than allowing for a little more variety in the portrayal of women’s lives.

However, it is with hope that the success of these Bechdel Test approved, female-oriented but widely enjoyed, critically acclaimed and commercially successful shows will encourage more of the same, featuring substantial female roles, significant female communication and women’s relevance to everyday life, to the result of more women’s stories being told (balancing out the male-centric programming currently aired), to the enjoyment of a mixed-gender audience.

Love the videos from Feminist Frequency! Thanks for running the test on the TV shows; I have two shows to add my watch-list.