Abdulnasser Gharem was one of the pioneers of what is recognized today as the contemporary art movement in Saudi Arabia. He was among the handful who, back in 2004, in a small hilly town called Abha, wrought up the vision that has slowly and irrevocably materialized in the Kingdom today as the dawn of a new era of art. What seemed like baby steps then, small but well-considered acts with far-reaching impact, proved to be historical strides. At the helm of things then and now, he creates ‘change’ through his art, not the radical and revolutionary kind that so many from the West would like to fit to Saudi Arabia, but a quieter, slower and deeper shifting of attitudes, the kind that he knows would suit his homeland where traditions running back to more than a thousand years are deeply venerated and still present and entrenched in daily life in so many ways.

Earlier this month, Abdulnasser Gharem’s facebook status read ‘I will say this a million times over – the real artist is he who creates change rather than talks about the need for change.’ That’s just the kind of thing he’s likely to be caught saying – short, direct, and striking. He has been called the ‘rock star’ of Saudi art because of his signature aloofness, his mixture of ruggedness and tenderness, and the special license of tolerance he seems to have earned for himself. He believes in change from the inside out, and in taking small but well-thought steps towards ideals and goals. In his practical hands-on art, he takes on Saudi Arabia’s social, political, developmental, and behavioral issues in works that sometimes involve a direct personal intervention in situations to raise the overall moral bar of conduct in society. As an artist, he sees his role as imparting instruction through creative means, pretty much like a skillful teacher knows how to get a point across slyly. His work combines a keen psychological insight with a great working knowledge of men and a confidence in new and experimental procedures.

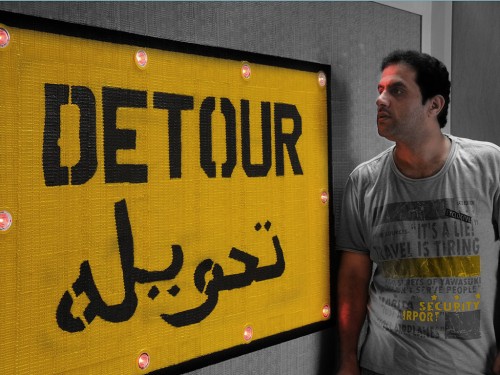

Abdulnasser Gharem uses the metaphor of road, journey, and navigation to address larger issues of the way that lies ahead for Saudi Arabia. His works demand a reappraisal of the whole notion of ‘development’ in Saudi Arabia, demanding more attention to the mind than to infrastructure and procedure. He tirelessly denounces herd mentality and insists on developing a critical perspective on things, questioning whatever context of beliefs and assumptions we are conditioned into believing. The leitmotifs he frequently uses, and the recurrent images in his work, add up to a visual alphabet of navigation itself. He finds the ubiquity of road signs and their linguistic pithiness amusing. The idea of road blocks, the expanse of roads, the aesthetics of its grey concrete, the charting of a trajectory across relentless terrain, the choice of direction take surface frequently in his work, and depict how Gharem’s imagination was influenced by the physical reality of a country in the throes of development. Distrustful of the visible or the obvious ‘path’ that we might take for granted, he re-navigates evolution using by-roads to define a trajectory that goes through the terrain of the mind, and overhauls the mental landscape.

His best works impact with a striking clarity and minimalism, and while originating from an intensely local context, catch on to universal realities. One of these is a work called Stamp, a metaphor for bureaucratic stalemate, one of the many roadblocks blocking the way towards change in Saudi Arabia. It consists of a giant wooden sculpture of a stamp reclining on the floor, and a seal with a text on a plastic disc on the floor. The seal reads ‘Have a bit of commitment, please’ and of course, ‘Amen’. This irony between the size of seal and the size of the ‘commitment’ required and the note of vague and indefinite deferral is common in diplomatic procedures in Saudi Arabia, and short of pulling one hair’s out, dealing with it using a tongue-in-cheek attitude is pretty much the only option that remains open to a thinking man. “In Saudi Arabia as in most developing countries, infrastructure-wise, a lot of things are completely state-of-the-art in the cosmetic manner of Dubai glossies, but the procedural complication of systems is still several decades behind. People should understand that their progress as nations is directly proportionate to the perfection and simplification of systems. The effectiveness of systems determines the fate of nations.”

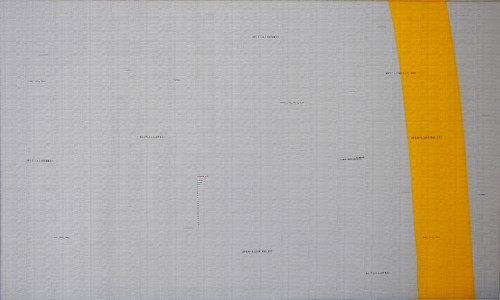

The metaphor of the stamp as a symbol of old-fashioned procedures, bureaucracy and useless formalities is extended further in his ‘stamp paintings’ where instead of the subject, it becomes a canvas, and the very act of writing or painting upon it becomes a silent rebellion. In these ‘stamp paintings’, entire sheets of plywood are covered entirely with letters from stamps rearranged to contain subliminal messages echoing themes of change, high idealism or mysticism – ‘The New World Order’, ‘Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, the rest are also not free’, ‘Commercializing’, ‘Don’t trust the concrete’. Against this background are sometimes drawn images suggesting high idealism or irony, a picture of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish or sometimes, a single yellow line called ‘Pedestrian Crossing’ to show a deliberate individual choice or ‘the road less traveled’. In other, more ironic and politically inclined stamp paintings, he shows a smiling Obama next to the caption ‘No more tears’, of which a second canvas reads ‘No or Bad signal’ when the promises become hazier post-elections and signals don’t flow as freely between rulers and people. At all levels, from the typographic rearrangement to the image superimposed upon the recreated ‘canvas’, everything adds up to an effect which is explosive in its force of hope.

Direction is a constant preoccupation with Gharem. In The Path, he merges the aesthetics of the familiar with an infinite overcharge of metaphor. For his performance, he uses the relic of a bridge whose history is obliterated from official records, but alive in popular memory through word of mouth. This dilapidated stub of bridge is in the Tihama region. In 1982, according to local legend, there was a flash flood in the region. As the water rushed in, people from the village, struck with panic, took the advice of one man who told them to climb the bridge for safety. Following him blindly, they clambered atop the bridge, huddling together for safety. In no time, the swell reached them, breaking the bridge they stood on and taking their lives. Gharem resuscitates both the stub of concrete and the stub of history. With a spray can, starting with his brother and recruiting a lot of eager volunteers along the way, he painted the word ‘Al-Siraat’ in white all across the grey cobalt of the bridge. The writing is in opposite directions in the two halves of the road, and from afar, looks like the ripples of water that inundated it so many years ago. The smooth, sturdy strip of grey suddenly drops into an abyss. Undercut by the reminder from local history with the white scrawls of ‘Al-Siraat’ covering its surface, the image posits the contrast between the concrete and the abstract, between the finite and the infinite. For our journey in life, we need faith in our heart more than the concrete under our feet. The visual starkness of the bridge shoulder dropping off suddenly: the deception of its toughness, and from another angle, the branching out of different roads under the bridge converge into a metaphor for choice- its necessity as well as its precariousness.

Abdulnasser Gharem has his facts right. He knows that the artists in Saudi Arabia enjoys the privilege of tacitly addressing issues that might be uncomfortable to broach directly or solve through conventional mainstream channels. Art is a by-road, a side lane; in a manner which is established, understood, and respected in Saudi Arabia, where an official censorship of ideas still prevails in mainstream media, and people are extremely cautious while expressing themselves, the artist can perform with an advantage of license. Gharem has earned himself this license. He sees the road ahead clearly, just as he sees the obstacles dotting it, and his role in the scheme of things as a leader.

All images by artist.

Leave a Reply