The Barnes Foundation has just reopened in a new gallery on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia

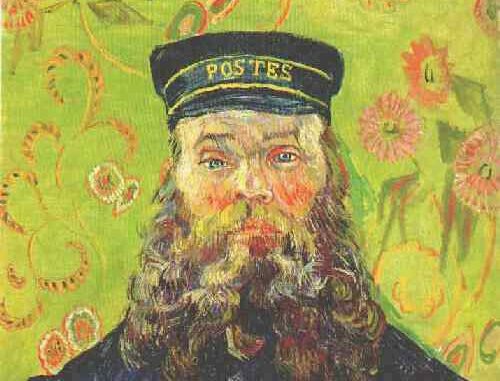

When I go art-gallerying with my brother he always asks to be taken to see the big-hitters. Not for him the minor works of lesser artists, what matters are the big works by great names – and getting to the cafe before it closes. If he made the same request at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia we would still have to visit every room – indeed we would have to look at every wall. Still we might not get out by closing time, such is the number of masterpieces that are on display in this fantastic gallery. Post-impressionist masters hang everywhere – and I mean everywhere, as the gallery is hung in salon style with works all over the walls, just as Dr Barnes left it when he died in 1951. Whether you are interested in seeing Van Gogh, Matisse, Degas, Renoir, Cezanne – the list goes on and on – then the Barnes will be a treat that you will long remember.

The collection was founded on the artistic nous of William Glackens – one of the United States’ leading modernist painters – whom Barnes had known at school. Having become rich from a patented medication for babies eyes Barnes sent his friend to Paris to buy up the latest works. Recognising that Glackens had the ‘best eyes in America’ Barnes gave him carte blanche – and a large pile of cash. Glackens loved the modernist experiments he saw in Europe and returned with thirty-three works that set the tone for the rest of the collection, and affected his own work.

Matisse’s large-scale Le Rifain assis is one of the first images you see when you enter the gallery. Dating from 1912 it is a souvenir from the artist’s time in Morocco. Filling the space between two windows the sitter stares down at you, filling the frame. The raised position of his serious expression gives a sense of power and controlled violence to the exotic young man. Matisse’s bright colours emphasis the otherness of the scene, the difference of the subject from the viewers then and now.

Apart from the salon style hanging there is another great difference between the Barnes Foundation and most other art galleries. This is the lack of name tags to help identify the works. ‘If it has ballet dancers it’s probably Degas,’ is the sort of instruction you hear issued and although it makes playing spot-the-artist harder, it allows people to enjoy the works for their intrinsic value, rather than for the mere name of the artist. The positions of works has not been altered in the new museum – the rooms are the same size as in the old galleries at Merion and all of the works remain in the same relation to each other. This means that Barnes’ idiosyncratic hanging system is still seen today. He seems to have adored order and hung his collection with an eye to symmetry of size and color. Sometimes he places something near a painting that relates to it – an ashtray near a painting of a woman smoking for example. Sometimes there is a theme running through all the paintings on a wall. What he doesn’t do is hang one artist all together.

In the main room he hangs two large masterpieces one over the other. Seurat’s Poseuses and Cezanne’s Les Joueurs de Cartes are both from the same period and show the way that art was developing around 1890. The composition of both paintings is pyramidal and Barnes is playing with the similarities and drawing out the differences. Whether he is also deliberately elevating feminine beauty over male ruggedness is unclear, but the muted, unfashionable gamblers do not come off well compared with the elegant strollers and nude models in the picture above. The subject matter may be humble but the Card Players is one of Cezanne’s major works, with versions of varying sizes in galleries around the world. By painting on such a scale (the width is almost 2 metres) Cezanne is seeing a grandeur in peasant life that was not universally recognised. Barnes has noticed a stillness in both pictures that is made clearer when they are seen together. Whilst this might be expected in Seurat’s reworking of the Three Graces, in the midst of a card game the calm is surprising. In this way Barnes’ hanging draws out elements of the paintings that might not otherwise be noticed.

In the main room he hangs two large masterpieces one over the other. Seurat’s Poseuses and Cezanne’s Les Joueurs de Cartes are both from the same period and show the way that art was developing around 1890. The composition of both paintings is pyramidal and Barnes is playing with the similarities and drawing out the differences. Whether he is also deliberately elevating feminine beauty over male ruggedness is unclear, but the muted, unfashionable gamblers do not come off well compared with the elegant strollers and nude models in the picture above. The subject matter may be humble but the Card Players is one of Cezanne’s major works, with versions of varying sizes in galleries around the world. By painting on such a scale (the width is almost 2 metres) Cezanne is seeing a grandeur in peasant life that was not universally recognised. Barnes has noticed a stillness in both pictures that is made clearer when they are seen together. Whilst this might be expected in Seurat’s reworking of the Three Graces, in the midst of a card game the calm is surprising. In this way Barnes’ hanging draws out elements of the paintings that might not otherwise be noticed.

Anyone who has had the briefest of introductions to late 19th/early 20th century art will be amazed at the work that is dotted around the walls. But Barnes was also active collecting furniture and ironwork from the Americas, and this is displayed amongst, around and below the European masterworks.

I doubt many people are visiting just to see the metalwork or furniture, but the carefully placed desks and hinges show a mind obsessed with symmetry and order and give an insight into the all-consuming passion that this collection became. A Windsor Bow-Back armchair sits underneath a Cezanne portrait. A metal escutcheon is placed next to a Van Gogh – which itself is hanging underneath a small Renoir! That is the way with the Barnes – keep your eyes peeled and don’t miss anything – because it’s probably a masterpiece.

The papers have tried valuing the Barnes’ collection and have come up with figures around $25 billion. That’s a lot of money to be hanging on the walls in a relatively small gallery in Pennsylvania and gives a materialistic idea of the demand for the sort of paintings that are on display. Artistic merit may not be measurable in dollars and cents, but price gives an indication of the regard that the world holds an artist – and the world holds the artists at the Barnes in very high esteem.

Click for more information about the Barnes Foundation, including opening hours and directions

There is just too much in the Barnes Foundation for just one article so stay tuned for part II!

Leave a Reply