Once upon a time, the soft thud of the post landing on the doormat was a sound synonymous with early morning routine. People would start their day by perusing the morning papers and opening the mail before heading out into the world of work. Now, they’re more likely to be sipping their morning coffee whilst listening to the incessant ‘ping’ of a mobile phone or the not-so-dulcet tones of a computer generated voice announcing repeatedly that: “You have email.” Not quite as poetic somehow.

According to 2014’s annual Post Office statistics, today, the average household only receives personal letters about once every seven or eight weeks, compared with once a fortnight back in 1987, and more than 80% of 16-year-olds in the UK said they have never written a letter.

Simon Garfield, journalist, prolific letter-writer and author of To the letter: A Journey Through a Vanishing World, believes this decline is due largely to the invention of electronic communication:

“Because of email, letters are dying out. We no longer write in any sort of depth. We don’t express our emotions as we would in a letter, simply because it’s easier not to. To the younger generation especially, the idea of taking the time to write someone a letter – going to the trouble of writing neatly, getting a stamp and an envelope and taking the finished product to a post box when you could click a button instead, seems almost ludicrous.”

Since the internet burst onto the scene in the late 1980’s and changed our lives for good, the old-fashioned written word has been forced to take a backseat. Nowadays, post-boxes and doormats across the globe are left empty and forgotten, whilst over in cyberspace, our mailboxes are overflowing with impersonal and often unwanted correspondence.

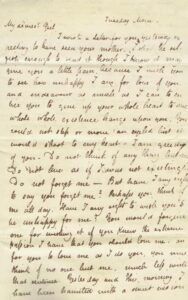

Up until a few years ago, the only person I knew who still wrote letters was my Grandmother. We would write to one another several times a week to give a little insight into the turning of our respective worlds. Then, in 2011 at the age of 73, she got a Macbook and a Facebook account and hasn’t written a single letter since.

Literary letters

Letters have always held great significance in the literary world. During their short courtship, John Keats wrote hundreds of love letters to his neighbour Fanny Brawne; Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford were engaged in a loquacious exchange of witticisms that spanned more than 20 years; and Sylvia Plath wrote enough ‘Letters Home’ to fill an entire book.

Saul Bellow, whose letters were published in 2010, was yet another ardent letter-writer; Graham Greene, Hemingway, Kerouac and Lord Byron were also partial to the odd epistolary exchange and Jane Austen even wrote the first draft of Pride and Prejudice as a collection of letters, in homage to the father of the epistolary novel, Samuel Richardson.

For modernist poet Amy Lowell, the act of writing a letter was like squeezing desire into little inkdrops and posting it. For Emily Dickinson, it was the route to immortality, and for John Donne, it was the mingling of souls.

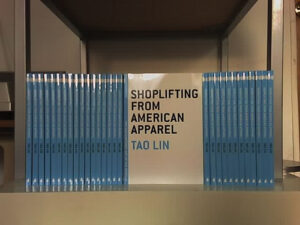

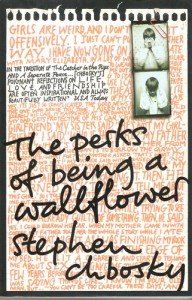

But when it comes to modern literature, even the epistolary novel seems to be a thing of the past. Stephen Chobsky’s 1999 bestseller The Perks of Being a Wallflower owes part of its popularity and uniqueness to the fact that it is written entirely as a series of personal letters, but that’s pretty much where it ends. Tao Lin’s 2009 novella Shoplifting from American Apparel is composed partly from the correspondence between two friends, but their medium of choice is Gmail ‘chat,’ not old-fashioned pen and ink, and Lauren Myracle’s Internet Girls trilogy is written from cover to cover in ‘text speak’.

But lately, it would seem that letters might just get their happy-ever-after after all:

“Living in a world where anyone can contact you at any time, where you’re expected to be available to ‘chat’ 24/7 and where you’re just not gonna make it if you don’t document your life on Twitter or Instagram, really does have its drawbacks,” says journalist and writer for XO Jane, Marianne Kirby.

Tired of the incessant and invasive communication made possible by the internet, many people are moving back towards letter writing, and opting for snail mail as their preferred method of communication.

For Mary Robinettte Kowal, founder of the annual ‘Month of Letters’ project, a month-long initiative designed to encourage people to switch off their technology and communicate instead using handwritten letters, the joy of letter writing lies in the element of surprise:

“Unlike an email, a letter is a ticket to the unknown, an insight into someone else’s consciousness, at a time when, of all things, they were thinking of you.”

A second-wind for snail mail?

Stephanie Jones, founder of non-profit organization ‘Handwritten Inspiration,’ which writes motivational and uplifting letters once a month to people anywhere in the world who are in need of help, turned to letter writing as a means of dealing with anxiety and depression:

“Six months ago, I started posting uplifting pictures or quotes on my personal blog and over time that developed into Handwritten Inspiration. I made a new Tumblr page which allowed people to submit their postal addresses so that people could write to them. Some people just wanted a friend to talk to and we started writing letters back and forth. Others just needed the comfort of knowing someone was there and was thinking of them. I feel you can only do that with handwritten letters.”

Stephanie said: “I think there will always be a place for letters. Whether you’re writing to your favourite band member or your best friend, letters mean so much more. The fact that you took the extra time to write what you wanted to say rather than typing it…that’s emotion that can’t be expressed through a screen.”

Perhaps there’s hope for letters after all. In a world that is fast becoming saturated with technology, the old fashioned ‘Dear John’ might actually be the most effective weapon of choice. Maybe Shakespeare was right. Maybe the pen really is mightier than the sword, and the Macbook, too.