I’m Going to Change My Name is the second feature by Maria Saakyan whose debut The Lighthouse premiered at London Film Festival in 2008. That film demonstrated a director with a keen sensitivity towards the subject of family ties and issues of identity and community in times of conflict, taking as its narrative conceit the story of a young woman returning home to a small village in Armenia. Again depicting the experiences of a young woman – this time fourteen year-old Evridika (Arina Adju) who is angry at her choir director mother for both her father’s absence and her own frequent time away due to touring – Saakyan rather excellently portrays the contemporary relationship with online space. Evridika is a filmmaker, shooting her curious perspective of the world using her mobile phone. She uploads videos to a suicide chat room – hoping to connect with other alienated souls. A screen shot depicting the absence of any responses aptly describes the loneliness of online communication, and later – having found someone to talk to – Evridika projects the screen image on the wall, making this seemingly small communication a huge icon of her ability to relate. Making the titular statement online – a space where the potential to create a new identity is spectacularly easy – Evridika expresses her need to take ownership of her origins, but beyond the free space for sharing and connecting on the web – a virtual transformation – Evridika wants to be reborn for real, and extends her connection with a fellow chat room user to ‘real’ i.e. offline space.

This simple plot forms the basis for some deftly handled non-narrative tangential sequences, Saakyan understanding her highly inquisitive central character and the daily, if not hourly changes of mood that come with adolescence. At the Q&A following the film Saakyan wisely avoided elaborating on the specifics of the similarities between her fictional character, and her own experience as a young woman, acknowledging that ambiguity is often the most rewarding aspect of personal filmmaking.

Making indiscernible, the line between documentary and fiction, realism and – for want of a better word – fantasy, was an aesthetic choice present in the three Thai films I saw at LFF this year. The highly anticipated Mekong Hotel by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, which screened alongside young, new filmmaker Vorakorn Ruetaivanichikul’s Mother both contained moments of a ghostly, spiritual or dreamlike presence, whilst Wichanon Somumjarn’s In April the Following Year, there was a Fire referenced the former director and employed a similar melding together of narrative with reflexive depictions of the activity of filmmaking. Mekong Hotel appeared as a sketch of a film and could be interpreted in many ways – one being perhaps a sequence of images to accompany guitar practice, or as the process of collecting stories from his regular cast that could form the basis of another film. Whatever it was intended to be – and being a fully realised concept such as Syndromes and a Century it was not – it at least whet my appetite for more Apichatpong.

Making indiscernible, the line between documentary and fiction, realism and – for want of a better word – fantasy, was an aesthetic choice present in the three Thai films I saw at LFF this year. The highly anticipated Mekong Hotel by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, which screened alongside young, new filmmaker Vorakorn Ruetaivanichikul’s Mother both contained moments of a ghostly, spiritual or dreamlike presence, whilst Wichanon Somumjarn’s In April the Following Year, there was a Fire referenced the former director and employed a similar melding together of narrative with reflexive depictions of the activity of filmmaking. Mekong Hotel appeared as a sketch of a film and could be interpreted in many ways – one being perhaps a sequence of images to accompany guitar practice, or as the process of collecting stories from his regular cast that could form the basis of another film. Whatever it was intended to be – and being a fully realised concept such as Syndromes and a Century it was not – it at least whet my appetite for more Apichatpong.

Mother is a highly personal portrait of the director’s mother and her experience of mental illness, which brings ethics into question. Ruetaivanichikul, or Billy – as he opted to be referred to at the screening – described how he intended the work, in part, to be a way of speaking to his mother. Whether she would appreciate the film is a question unanswered and a thought that I couldn’t shake during its screening. Favouring extreme close-ups and long takes, Billy’s camera is shockingly revealing about his family’s treatment of his mother. Once scene in particular – a long, static take of Billy’s mother crying after being scolded, only to be scolded further by his sister, shows the frustration and lack of, if not compassion, understanding for her mothers feelings.

This stuck a chord with the audience, and during the Q&A questions were raised about Billy’s decision not to cut. In answer, he described how he switched on the camera and then left the room and was later affected by the revelation of the change in his mother’s mood over time. With some gorgeous symbolism and ‘dream’ sequences breaking up the documentary sections of the film, I have no doubt that Billy’s intentions were sympathetic to his mother, nevertheless I couldn’t help feeling uncomfortable with how exposed she appeared to be, and wondered about the issue of consent.

Also dealing with family dynamics was Barry Berk’s debut Sleeper’s Wake. Screening in the First Feature Competition, the film is a raw depiction of grief centring on a man whose wife and daughter are killed in a traffic accident. With powerful opening scenes, Berk achieves a mood of total despair, framing his protagonist in minimal interiors and a palette of silvery blues as he deals with his literally broken life. John (Lionel Newton) at first attempts to heal gradually, with liberal doses of alcohol to numb the pain, but upon meeting another family recovering from the death of the mother, he is wrenched from gentle coming-back-to-life to outright primal survival. This makes for a pretty heavy-handed treatment of the transitions of coping, as though John not only has to wake up, but return to primitive instincts in order to go on living. Regardless of that, it’s a very strong debut and a stunning depiction of South Africa’s coastal region.

Also dealing with family dynamics was Barry Berk’s debut Sleeper’s Wake. Screening in the First Feature Competition, the film is a raw depiction of grief centring on a man whose wife and daughter are killed in a traffic accident. With powerful opening scenes, Berk achieves a mood of total despair, framing his protagonist in minimal interiors and a palette of silvery blues as he deals with his literally broken life. John (Lionel Newton) at first attempts to heal gradually, with liberal doses of alcohol to numb the pain, but upon meeting another family recovering from the death of the mother, he is wrenched from gentle coming-back-to-life to outright primal survival. This makes for a pretty heavy-handed treatment of the transitions of coping, as though John not only has to wake up, but return to primitive instincts in order to go on living. Regardless of that, it’s a very strong debut and a stunning depiction of South Africa’s coastal region.

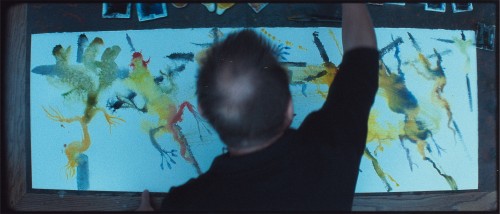

Grief was also the central concern in The Dream and the Silence directed by Jaime Rosales, a gorgeous and heartbreaking film about an unexpected death in the family screening in the festival’s Experimenta pathway. Shot in black and white and framed with colour sequences of painter Miquel Barceló at work, Rosales film uses its drastic sound design to emphasise the film’s theme of presence/absence. This vigorously formal creativity allows each sudden passage of silence to fall like a dead weight, deafening and devastating the previously happy family.

Much like Mekong Hotel, In April… and Mother, Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours defied the kind of easy categorisation of ‘documentary’ or ‘fiction’, and demonstrated his uncanny ability to cast both totally remarkable, naturalistic performers and discuss, or even dissect, cultural, national and personal interactions. Ostensibly about a middle-aged Canadian woman who is called to Vienna when her cousin is taken into hospital, what follows was best described by the director – during his introduction to the film – as a conversation, about art, life, memories and generally all the things that allow us to connect with one another. Set mostly in the Kunsthistorisches Art Museum, the film uses voice over from the museum guard, Johann (Bobby Sommer) as an almost meditative reflection on his encounters with Anne (Mary Margaret O’Hara), whom is feels inexplicably drawn to when first she wanders into the museum.

That one can feel both a visitor to the museum and an eavesdropper on Anne and Johann’s conversations is testament to the deft way in which Cohen handles the overall tone of the film – steady and sometimes distant. This provides for fascinating viewing, for example the discussions of Pieter Breugal by a museum guide and her visitors about the unexpected focal point of the artists busy paintings, becomes a analogy for the experience of viewing a Jem Cohen film – that an artwork’s meaning may come from different and unexpected places that you first assume. Ultimately, it may just have been my favourite film of LFF 2012.

Leave a Reply