Perhaps the most famous director to equate film and therapy is Woody Allen. An unlikely source for Palestinian director Raed Andoni to draw on in his documentary Fix Me. Yet parallels between the two directors show this film subverts audience expectation and refuses to be affiliated with political struggle.

The audience is glimpsing an emphatically private life. We are introduced to Andoni as protagonist by intruding on his therapy sessions. He is a film director with ‘a tension headache’. He insists he ‘cannot identify with groups’ and ‘blow[s] a fuse when people try to frame me within a concept’. Crucially, his personal progress and despondency is compelling and the viewer relates to Andoni as one human being to another. The most determinedly apolitical scene shows him bored, alone and playing his voicemail’s mantra ’no message’ on repeat.

This rejection of politics is most emphatic in an interview with an electrician re-wiring Andoni’s city centre apartment. Beaten by Israeli captors so badly he was thought dead, the electrician credits his survival to a ‘need to be strong’ bred by environment. Andoni replies that he feels a ‘right to be weak’ and tells his therapist he feels lucky in contrast.

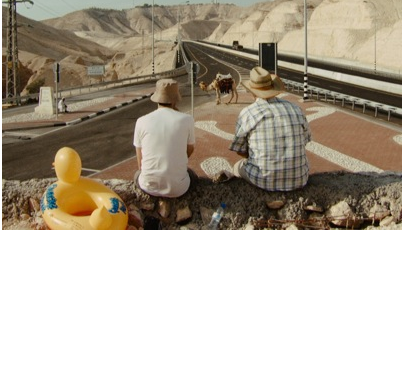

Yet ‘we need a frame. Your headache’s a frame’. His sister’s argument heralds a turning point in Fix Me. Framing is inescapable. Shots of desert, towns and checkpoints are edged with a BMW windscreen. The crew films through the borders of the doctor’s window. Perception is framed. Acknowledging and lampooning this, the film can explore the individuals within, yet crucially separate from, Israel/Palestine conflict. Poignantly, Andoni and his friend, beachwear donned, dangle their bare feet over rocks. The camera pans out and the audience sees they are perched on the landlocked concrete ‘sea-level’ marker. The lapping waves and seagull cries are a soundtrack. This is the closest they can get to a coastal holiday under Israeli occupation.

The film’s climax is his visit to an old cellmate. Andoni ferociously dissects his friend’s statement ‘we never yielded’. We find out that his personal ambitions for higher education yielded to activist work for Palestinian freedom. This is the central tension of the film; is individual freedom is possible without collective freedom? Andoni protests, ‘I have no answers. Just questions’. Because, fundamentally, ‘I’m not a minority, I’m a person’. So why shouldn’t this middle class, educated filmmaker relate to a Jewish film-director living in New York? Woody tells us ’94.5% of statistics are all made up’. Raed Andoni escapes being a statistic.

Leave a Reply