There are currently two one-man exhibitions devoted to portraits at big London galleries. Skip the National Gallery’s repetitive Goya extravaganza and visit the far more interesting Giacometti: Pure Presence at the National Portrait Gallery. Giacometti is celebrated as a modern sculptor but his portraiture is less well-known. The NPG have brought together over sixty paintings, sculptures and drawings from across his life, showing his interest in the human face and its connection to a world of pain, anxiety and loss of innocence.

Alberto Giacometti’s early portrait paintings are staunchly fauvist, the bright colours and broad strokes betraying the influence of his post-Impressionist artist father Giovanni Giacometti. But the second room of the show (the route is not clear – take the first right to see the work in order) shows his attempts to find an artistic language of his own. His early drawings do not thrill, but show the genesis of the wild searching mark-making he would come to use. Later in the show his expressive lines will build up images whilst deliberately sabotaging any chance of clarity, giving a sense of viewing pictures through a fog.

His sculptures from this early period comprise heads of different sizes, different media and different styles as he experiments and searches more successful in three dimensions. A flat and engraved bronze head of his father from 1927 is the first sign he was onto something new. Reminiscent of ancient Egyptian flattened depiction he ignores centuries of historical precedent to create an unflattering portrait. It is aggressive, his father’s features crushed and compressed as though his morning routine involved shaving, cleaning his teeth and then ironing his face.

The show demonstrates the influence of place and atmosphere in art. Giacometti was making experimental work in Paris but when he returned to his family in Switzerland his work encompassed more traditional portraits. During the war his figures became more anonymous. He started working on a scale so small the pieces could be transported in matchboxes (though none of these are in the show). His signature elongated figures were a reaction against these tiny works, and the tall Woman of Venice VIII is exhibited to show the direction his work most famously took.

The show suffers – as many exhibitions do – from the oh-too-common art gallery decision to show a film in a room with only enough spaces for a few people to sit and watch a film. And even those lucky, seated few are in discomfort as the seating is usually actively uncomfortable. Here four can fit on the wooden bench in front of the TV. Everyone else stands until they get tired, blocking the room which is also full of old photographs of Giacometti at work and play. There’s no indication of how long the film is and the surrounding standers pounce every time a sitter leaves. Getting a seat becomes more important than watching the film. Bad sitting techniques start to annoy. ‘Budge up!’ you feel like saying, ‘There’s room for another.’

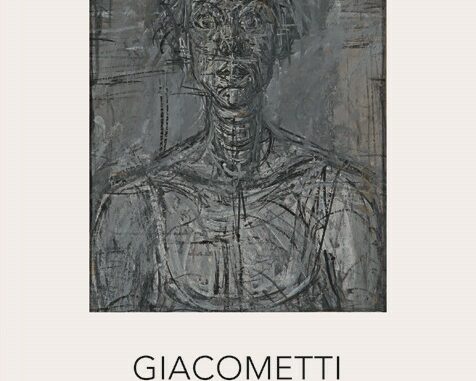

The 2D work at its best is vibrant, exuberant and anxiety-ridden yet it repeats too often – no matter who the model – the same staring features and wide-eyed techniques and captures little of the sitter’s personality. In the paintings the figures shrink and get lost in the canvas, culminating in Grey Figure where the universe and the human have almost become one overworked mass. Some drawings in the exhibition don’t excite at all (Louis Aragon for one), delineating form in a precise and too obvious way. The sculptures are most interesting, managing to combine Giacometti’s nervous, fidgety planes with differentiated faces.

The best room is out of order career-wise and is reached through room 2. Containing images of his mother this suddenly introduces his late style with withered heads and swirls of descriptive lines building up the unclear figures in wild surroundings.

Well-curated by Paul Moorhouse Giacometti: Pure Presence is a fascinating exhibition which shows the changes and developments in an artist’s career and so is interesting whether you know much about Giacometti or not. Like the nearby Goya show there are passages of too many, too similar images but here Giacometti demonstrates his more varied arc. He gets stuck in a re-working/over-working method that renders the faces of his models anonymous, and the sheer quantity of works actually takes away some of the power of the single images. But this is a show that can be recommended.

15 Oct 2015 – 10 January 2016

Leave a Reply