If you don’t know what happened to war poet Wilfred Owen then the title you’ve already read contained a spoiler.

Poets are often regarded as effete chaps who spend their days weeping about the futility of life, chasing clouds up mountains or capsizing in foreign lakes. However there was a period when poets came over all macho and you couldn’t stop them joining the army. Between 1914 and 1918 everywhere the British military went there was a poet versifying whilst trying to fire a rifle or put on a gas mask.

One of the most famous of these Soldier-poets was Wilfred Owen, author of poems such as Dulce et Decorum Est and Anthem for Doomed Youth. He is commemorated by a plaque in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner, but he is actually buried near the small village of Ors in Northern France.

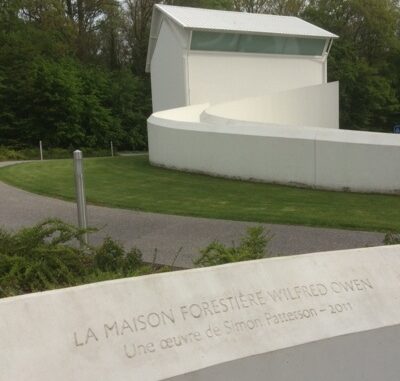

La Maison Forestiere, Ors, where Owen spent his last night

Although it was a war of diabolical misdirection, waste and idiocy, WW1 military records are surprisingly thorough. So we know exactly where Owen spent his last nights, what his company was trying to achieve and where he died. Now in the 100th year since the start of the First World War, the long-term mayor of Ors Jacques Duminy has completed a project to honour Owen’s last hours.

A seven kilometre walking route begins at the small cellar where Owen was billeted with at least 12 other men. You can download English audio guides that tell you about every part of the route here. The brick-lined cellar is underneath the Foresters’ House and has been left as it would have been in October 1918 – except for a loudspeaker broadcasting Kenneth Branagh reading Owen’s last letter to his mother.

The house above has been altered by Turner prize nominee Simon Patterson. Outside it has been painted white and the roof redesigned as an open book. Inside it is one big double-height room, again painted white but with handwritten quotations from Owen’s poems on the walls. The lights dim and Kenneth Branagh starts up again, along with projections of the text. These force you to look upward and move around the space as the words appear high on different walls, the calm atmosphere emphasising the poetry. The room is also used for cultural events, which presumably explains the minimal intervention. You don’t really have to be a Turner prize nominee to paint a house white, lower the lighting and press play on an audio track.

The walk follows the route that Owen would have taken on the 4th November 1918, when his regiment was ordered to cross the Canal de la Sambre-L’Oise. Now it is a pleasant stroll through the Bois-l’Eveque forest, although you need your eyes peeled for the path’s many twists and turns. There are small yellow markings on trees which show you where to go, but they are hard to spot. We went wrong almost immediately, and that was without a war on. Owen and his men made it to the canal, which was exposed to the machine-gun fire of German soldiers in a farmhouse on the other side. The route passes a typically beautifully kept British cemetery, but oddly it is not here that many of the soldiers are buried.

Just when you are expecting to reach the canal where the action took place you come to some water. It is only a narrow stream and for a moment I wondered why there was so much fuss about capturing it. Owen’s grandmother could have leapt it in a single stride. However a few metres further on is the actual canal. Rurally peaceful now, it would have been a huge undertaking to cross it under enemy fire. Commander Colonel Marshall had warned it would be very difficult, and as they tried to build a temporary bridge Owen and his men were cut down.

Owen died here, but the walking route follows the canal south-eastwards before heading to Ors’ tiny main square and the community cemetery. Here Owen and the other casualties are buried, at the far end on the right. The number of limestone gravestones makes it clear that Owen was only one of many men who gave their lives at Ors on the 4th November. As the most famous victim his story helps to bring attention to them all, their sacrifice made all the more pointless as the Armistice was signed a week later.

The walk in the footsteps of Wilfred Owen makes a surprisingly pleasant experience out of one of the many horrific events that made up WW1. Keep an eye out for the signposts but if you do get lost ask for directions to the canal. If you’re trying to get back to your car at the Foresters’ House ask for directions to the train station. From there the path is fairly obvious.

World War One saw a whole bunch of poets don the uniform of the British army. No doubt some poets donned the uniform of the German army as well, but to the victor the spoils and the posthumous royalties. [Remember to add the names of some German War poets here to try and look intelligent]

An online biography of Wilfred Owen

Opening hours:

The Foresters’ House is currently open as follows:

From April 15th till November 15th…from Wednesday to Saturday……from 2pm till 6pm.

Plus on the first Sunday of the Month from 3pm to 6pm.

Directions:

By car – approach from Cambrai on the D643. After Le Cateau take the first left – the D959. You will see a white house on the right by an old Camp Militaire.

The Flaneur travelled to France with MyFerryLink

Many thanks for the details you’ve given here. Indeed, the war that is shocking our peaceful life in Yemen reminds one of those war experiences many poets have turned into poems.