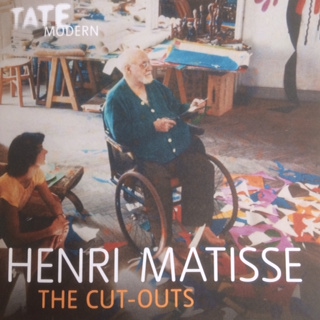

Once he’d abandoned his law career and discovered art Henri Matisse couldn’t stop creating. This is good news for lovers of his bold, fresh works, but also for art museums looking for ways to put a new twist on shows of his work. The Cut-Outs at the Tate Modern (until 7th September) focuses on work he made in the last years of his life. The leaflet handed out when you enter the show makes his age and disability apparent – an old man sits in a wheelchair wielding a pair of scissors.

He is surrounded by off-cuts – some of which make it into the show as a paint chart of his favoured gouache colours. It will make people disappointed they can’t walk into Homebase and chose a colour from the Matisse Range for their sitting room. His facility with the large shears is brought to life in the first room of the show, where a very short clip of 16mm film shows him chopping confidently at a sheet of gouached paper held by his assistant. (Even though it is only a short film the bench provided to sit on is comfortable – other galleries take note).

Matisse is known as an innovative painter of joyous images but ill-health towards the end of his life prevented him from continuing painting. The direction that his work took will already be known to many visitors to the show as since 1962 the Tate has owned one of his large scale gouaches découpages called The Snail.

To make this and the other works in the show Matisse stopped painting and started snipping. He cut and tore at sheets of paper that had been colourfully painted by assistants. He created shapes which he placed, or had placed, on the walls of his studio. The technique allowed for the images to be moved around until he was happy with the composition. Many of the shapes still have little pin-holes, showing that they were moved and replaced many times.

This was not a completely new development. Matisse had first used cut out shapes as a means of deciding on the composition of his paintings. This is made clear in the display of the painting Still life with Shell which is shown along with a similarly titled, similarly sized mock-up of the painting. In the mock-up the main components – coffee pot, jug, apples, etc have been recreated on paper to allow the artist to move the elements around before finalising his oil painting.

As he aged what began as an unseen back-room technique became the artwork in itself. His book Jazz was instrumental in this transition. Printed from small-scale cut-outs it revealed to Matisse that the original cut-outs had qualities that were lost in the printing. The Tate show has a room devoted to the printed pages of the book, displayed with the original cut-outs above. Such a number of images are not needed to make the point that it is the cut-outs that remain boldest and brightest – a vital discovery for an artist who dealt so strongly in vivid colours.

The show confirms that Matisse was not afraid to turn his hand to anything artistic, each new project fully grabbing his attention and being pursued with enthusiasm. He enjoyed improvisation – documentation about his work for the chapel at Vence shows the long charcoal/bamboo sticks he invented to allow him to work from the floor whilst drawing high on the wall.

The size of the show has needed careful curation, and the movement between different phases of his work has generally been well-achieved. Many large-scale works have been borrowed, but The Snail remains the star.

An app accompanies the exhibition and includes commentary on key works, insights from the curators and Matisse’s biographer as well as images of the artist at work in the studio. You can find it on the app store and Google Play.

Leave a Reply