Dennis Hopper would have loved Instagram. The actor wasn’t just a camera-toting hippie in Apocalyse Now – he took photography seriously between 1961 and 1967. It was an early-career fad – in this period he took an estimated 18,000 pictures. When he started directing Easy Rider in 1969 he put down his stills camera for good. He later turned to other art forms but left his interest in photography with his gelatin-silver prints in a box in his garage.

In 1970 Hopper himself picked out 450 of the images he had taken for an exhibition in Fort Worth, Texas. They were mainly 24x16cm – not a particularly large size for exhibition – and they were never displayed again during his life-time. After his death, when he was no longer around to veto a show, they were found amongst boxes of Christmas decorations. Now they have made it to the Royal Academy where they are on display in an attempted recreation of the original Texan exhibition.

Hopper’s love of snapping everyone around him anticipates our current obsession with recording everything that happens and putting it online. Photography is much easier and cheaper now, but Hopper was taking the same sort of pictures of mates, surroundings and street scenes that thousands of people take today.

Where Hopper’s pictures score is in the access that he had. His mates were film stars. His surroundings were film sets or trendy galleries. Given his career as an actor, Hopper was naturally surrounded by famous people. He didn’t seek them out, and even began to shoot portraits of actors for Vogue. He also shot artist portraits for exhibition invites for the Ferus gallery in LA. These shots of famous artists and actors make up the first section of the show. They are a document of a period, showing big names such as Messrs Oldenberg, Duchamp and Hockney, as well as Tina Turner, John Wayne and Paul Newman. He captures Andy Warhol with his 8mm camera, a youthful-looking Peter Blake.

A foray into photojournalism brings a few shots of Martin Luther King speaking to a crowd and some images of girls playing in a derelict street. A seamstress at work through a window. A girl cuddling a dog by a fire hydrant. He gets more interesting when leaving the famous faces behind and taking candid street shots, such as a man weighing himself – which lets the mind wander and start postulating all kinds of possible narratives.

Photos from a protest are not special and they lose a lot of weight when at the end of the show you discover the protests were about the opening hours for nightclubs. A mechanic leans so far into a car’s engine that his feet are off the ground. Clothes full of holes drying on a washing line speak eloquently of American poverty. A child’s doll floats in a swimming pool like that embodiment of the American dream, Jay Gatsby.

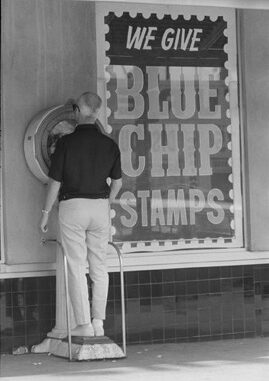

Dennis Hopper, Untitled (Blue Chip Stamps), 1961-67, Photograph, 24.97 x 17.12 cm, The Hopper Art Trust, © Dennis Hopper, courtesy The Hopper Art Trust. www.dennishopper.com (It is a condition of using the image to put this long credit)

The exhibition is made up of several different sequences – celebs, hippies, Hells Angels and more. Whilst each of these clearly needs to be kept together, there is no reason to strictly follow the way that Hopper laid out the show. That would have been site-specific and at the Royal Academy it results in only two or three walls being used in each room. The others are stencilled with quotations in the the sort of big letters that curators think are all that people can read nowadays. Why, after centuries of reading books and paper would humanity suddenly prefer to read walls? Better use of the space would have made it less of a queue-to-view exhibition, with visitors walking joylessly in a slow line around the exhibits.

Leave a Reply