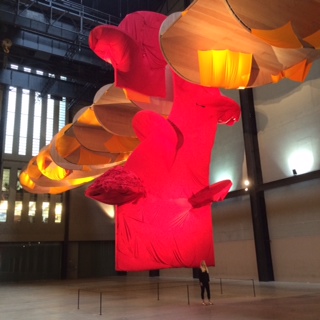

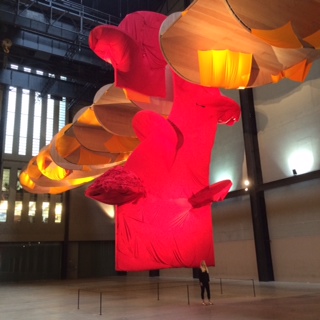

Large teardrop-shaped pieces of wood now hang in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern courtesy of the artist Richard Tuttle. Working on a much larger scale than he ever has before the piece looks like the internal skeleton from the wings of a lopsided plane. All over the fuselage orange sheets have been attached like sticking plasters to dangerously mend holes we can no longer see. A child’s soft-play engine hangs from the wing in red material. Suspended like a relic this could never fly – just like Tuttle’s own aviation history. Decades ago the artist signed up to become a pilot with the US airforce, but for some reason had not realised his job would involve dropping bombs. When this reality struck him he pulled out.

The piece brings together three specially-made fabrics to create different textures and is a bright beacon of colour in the dark Turbine Hall. Indeed, walk around it and the light from one spotlight will hit you right in the face, stinging your eyes and affecting your vision. It’s not a napalm bomb, but it’s not pleasant.

Richard Tuttle’s I Don’t Know. The Weave of Textile Language is concerned with the artist’s life-long interest in textiles. Textile is often associated with craft or fashion, but of course woven canvas is an important component of many of the world’s most revered works of art. The show centres on a broadly defined use of fibre, thread and textile and offers the UK’s largest ever overview of Tuttle’s influential body of work.

The survey of his work is composed of three parts, the first of which is the new work exhibited in Tate Modern. The second is a book of the artist’s personal collection of textiles and images of work. The third is a retrospective of his work from 1967, being held at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Pace gallery claim Tuttle is ‘one of the most significant artists working today’. He first came to prominence in the 1960s, his work using humble, everyday materials and combining sculpture, painting, poetry and drawing. When he’s not creating huge pieces for post-industrial Modern Art galleries, he creates art that can be easily overlooked – out of what is easily overlooked.

The first group of works to be seen are labelled 16 of 22 – the work is not hung chronologically, the labels indicating where they come in Tuttle’s large oeuvre. A series of very small shelves each holding a small piece of wood and some detritus – maybe blutac, paper, thread or wire. Screwed to a beige support they are small, delicate, fragile, deliberately slap-dash and dull. With names like Section VIII, extension D they don’t easily give up any meaning beyond their reuse, recycle method of construction.

The artist’s labels are a definite part of the show, large, obvious and containing not only the usual information about the piece but also a poem. However some of the Whitechapel’s explanatory signs lapse into confusing art-speak. One near Third Rope piece (1974) assures the viewer that a 5 cm piece of white rope nailed to a wall ‘encompasses the space.’ If that makes sense it needs to be better explained.

Other work includes collages, sculptures, and Ten kinds of memory and memory itself – ten pieces of string placed on the floor. Another – Fiction Fish I, 7 – is a wall painted a slightly different colour to the rest of the gallery. On it a small sculpture of graphite and ribbon sits an inch off the ground, from which a graphite line leads up to the ceiling. In a separate room are some Tuttle ephemera, old exhibition invitations and artist books. He has many different means of working, most interestingly in wire in a series of pieces made by connecting a piece of wire to the start and end points of a line drawn on a wall. Having forced the wire to follow the line of the pencil on the wall, Tuttle then allows it to spring away, leaving a wavering shadow and a sense of lack of control.

But neither the work at the Tate or at the Whitechapel is must-see. Tuttle’s work may be historically important and he may have influenced many other artists, but the stream of deliberately haphazard-looking pieces is aimed squarely at the deeply-invested Tuttle-buff curator or collector.

So should you visit? Here’s a handy way to decide whether a trip to Aldgate East is worth your time. What’s your reaction to the following true story?

A sheet of pale, dyed material (Purple Octagonal, 1967) hangs on the wall upstairs at the Whitechapel gallery. It is roughly octagonal and is nailed at the top, but not at the bottom. The curator points out that the bottom hangs free from the wall. He comments on the slight shadow that can be seen there and suggests the piece should make you have some curiosity about what is behind.

If you feel you would be curious about what is behind the bottom of a hanging piece of pale, dyed material then you’ve just found your show of the year. Hurry to the Whitechapel. If you think it’s almost certainly more wall, this show is not for you. Of course there is an art-historical interest, Tuttle being one of the first artists to make what was then a radical gesture and liberate canvas from stretcher. But this is serious work that is more interesting for curators to theorise about than for most people to see. Read up on Tuttle before you go.

Leave a Reply