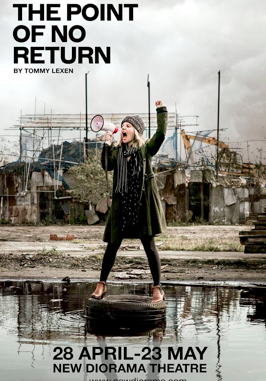

As we approach the election we tend to be cynical about politics in the UK. Let’s be grateful we don’t live in the Ukraine. However tight our vote, there’s little chance of a subsequent revolution, of a leader poisoned and disfigured by Agent Orange, of his successor ordering snipers to shoot unarmed protestors, or a foreign power stirring up a civil war to kill thousands. That’s the story of recent Ukrainian politics, and the subject of a brave new play by Tommy Lexen.

Nigel Farage should reflect that people on the other side of Europe are dying for the chance to join the EU. When people take to the barricades to fight for straight banana regulations and a common fisheries policy you know the alternatives must be bad. The history of Ukraine – the very name means ‘border-lands’ – is a litany of horrors. Huns, Vikings, Mongols, Cossacks, Ottoman slavers and Tsarist tyrants were merely a prelude to the Soviet Terror-famines and Nazi ‘Extermination War’ that it suffered in living memory. Then, last year in Kiev, a corrupt president in thrall to Putin fired on pro-European protestors in Maidan Square.

Lexen’s play is based on eye-witness accounts and ‘developed with academics and political experts’. It catalogues the events of the days of protest that led a government to use live-fire against its own people: the title’s ‘point of no return’. The key scene where the decision is taken is one of the least dramatic. The moment’s mundanity seems plausibly sinister: choices like that are made by men with no sense of their political or moral magnitude.

The ordinary characters caught up in the mayhem that follows bring a welcome human dimension to events we glimpsed remotely on the news. Particular praise goes to Haakon Smestad’s equally convincing performances as abused protestor and government thug, to Jodyanne Richardson’s sympathetic university lecturer, and to Vikah Bhai. His conflicted policeman – defending what was after all an elected government – brings welcome balance to the play. Once politics is replaced by violence, even the forces of repression can be victims. The cast is helped by a powerful soundscape created by Ben Osborn, which makes imaginative use of the disorientating noises of a modern revolution. In all the result is an intense immersion into the heart of a revolution.

This is no ‘Chimerica’ (a play which placed the equivalent moment of the Tiananmen Square massacre on a broader political canvas). Nor are there many moments of dark humour amidst the violence – I longed for some touches of that great Ukrainian, Gogol. Like the Euromaidan movement itself, this play is scrappy and a little disorganised, but its heart is in the right place. Perhaps these events are still too raw for a full artistic response. Or perhaps the sponsorship of the German Foreign Office and of organisations like the ‘British Ukrainian Society’ raise a slight question about the political funding of the piece. But, living in a free society, we all know the truth of what happened in Ukraine. And – however cynically – we can at least choose our politics without the threat of state violence. If you need a reminder how much your vote is worth please go and watch this play.

by A N Donaldson

Leave a Reply