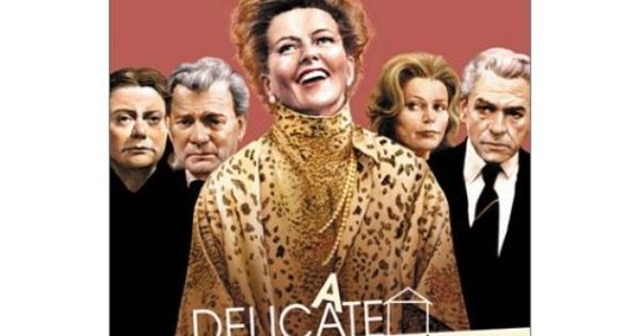

With Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Eugene O’Neill, and August Wilson, Edward Albee is most likely to sustain a position in history as one of the five greatest American playwrights of the 20th Century. A Delicate Balance (which shows more cousinage with some of Beckett’s and Pinter’s works than with those of his American confreres) is considered by many theatregoers and critics to be his masterpiece. It premiered on Broadway in 1966 and over the past 50 years has been revived in stellar productions in London and New York and around the world. A superb 1973 production—directed by Tony Richardson and starring Katharine Hepburn, Paul Scofield, Kate Reid, Lee Remick, Joseph Cotten, and Betsy Blair—is one of 14 major plays filmed by the American Film Institute between 1970 and 1975 and available now in a DVD box set and through several streaming options.

Albee’s elliptical yet densely packed examination of loss and fear was set in the present, but it’s a present that after five decades continues to feel both immediate and yet at some slight remove from any time we know. The play exists in a sort of unsettling timelessness of existentialist absurdism, despite the fact that the physical setting is the large, elegantly wood-paneled library and living room of a grand old house in some upscale exurb of New York City (or, just as easily, London). There are flashes of scathingly ironic humor—even real funniness—but just beneath the tasteful well-ordered surface of this household, there are histories of lost children, lifelong friendships that provoke rather than nurture, icy marriages, infidelities, festering secrets. Life-and-death battles are being waged that on this particular weekend erupt into the open. Even as it operates as a satire of all those taut drawing-room comedies of the 1920s and ’30s by Maugham and Barry A Delicate Balance is also a nightmarish horror story.

As Agnes (Hepburn) and Tobias (Scofield) settle in for a post-prandial drink, we know that this Friday evening is one of a long-years tradition of such evenings. Agnes is handsome, well-dressed, dignified, and articulate. Her first lines are long, Wildean or Jamesian; her sentences become paragraphs, discursive and at times oblique, but never wholly off-topic. Her initial topic unfolds as a gently musing and bemused aria in which she considers the possibility of whether or not she may someday go mad—nothing dramatic, more a slipping away, an unmooring. Tobias is handsome, also elegantly dressed. He listens rather impassively and makes occasional, low-key responses.

More concrete problems arise in the form of Claire, Agnes’s sister (Reid) who lives with them. A brashly self-proclaimed “drunk” who disparages the term alcoholic, Claire’s only idea of a good time seems to be to redirect occasionally her self-hatred into embarrassing Agnes and commiserating with Tobias. Then Julia (Remick), Agnes and Tobias’s only surviving child, fortyish, returns home after the collapse of her fourth marriage. The final ingredient in Albee’s mixture of desperate humanity and brutal comedy is the arrival of Agnes and Tobias’s best friends Edna (Blair) and Harry (Cotten). Occupied with quiet pursuits—hers needlepoint, his French lessons—after dinner in their home nearby, they were suddenly overcome by an ill-defined terror so potent that they dropped everything and, without calling, arrive on their friends’ doorstep seeking refuge. Agnes and Tobias find such behavior odd, perhaps even peculiar, but after all, it’s only for one night; they welcome Edna and Harry who, from the moment of their appearance, begin oddly to act as if they belonged there. The next day they announce that they’re moving in permanently.

The terror is never explained but, as with good poetry, the ambiguity in A Delicate Balance is the result of neither fuzzy thinking nor contrivance. Albee creates an imperiled sense of civilization that has variously but persistently gotten under the skins of audiences. The dialogue crackles with an arch grotesqueness, small-talk on the surface and disorienting philosophical probings underneath. Yet the challenged sense of self-determination and privacy, the fragile bonds of intimacy, and even the occasional insularity of these characters grant them a curiously spellbinding power.

Albee wrote, in a 1996 preface to the play, “(it) concerns . . . the rigidity and ultimate paralysis which afflicts those who settle in too easily, waking up one day to discover that all the choices they have avoided no longer give them any freedom of choice, and that what choices they do have left are beside the point.”

Whether it is the incursion of increasingly pervasive anomie, free-floating anxiety, or a loss of direction and purpose, the characters and—through the powerfully involving dramatic bond Albee establishes—the audience confront together an unnamable but inescapable sense of dread. Agnes recognizes it as a kind of plague, Claire feels that on the battlefield of her life she has earned a right of immunity, Tobias worries what his responsibility in aiding the two victims should be, and Julia is merely enraged that Harry and Edna have taken her old room. (Audience members will likely be filling-in their own blank canvases, at once individuated yet perhaps not unrecognizably dissimilar to their neighbors.)

The play has likewise offered some of our finest actors latitude for interesting choices about when to play up the black comedy, when and how to reveal the despair—and there have been some uniquely superior productions of this modern classic over the years. Jessica Tandy originated the role of Agnes, and she has been followed memorably by Rosemary Harris, Eileen Atkins, Penelope Wilton, and Glenn Close. George Grizzard, Tim Piggott-Smith, and John Lithgow have played Tobias, and Maggie Smith and Imelda Staunton and Elaine Stritch, Claire.

Director Richardson evokes Hepburn at her best in this filmed version. Her Agnes is simultaneously a strong and self-possessed patrician and a wife and mother who is clinging by her white-knuckled wits to her sanity and existence. Hepburn inhabits the playwright’s stillnesses with eloquent emotional reserve and enlivens Agnes’s fear with the incisive humor of a survivor. Scofield takes Tobias from a rather laconic man carapaced in effete weltschmerz to a deeply sympathetic human struggling to find meaning, if not in redemptive action at least in intentional commitment. Reid’s Claire is etched in acidic blood-and-guts: it’s a ferocious performance that manages to sustain a touching vulnerability. Remick gives Julia’s spoiled-rotten immaturity a surprisingly wistful tenderness—we understand her need to harbor away from the storms in defiant shallowness. Blair, and especially Cotten (in one of the best performances of his career), as the bizarrely fearful suburban refugees, are at once pitiable and sinister.

Richardson avoids the most common hazard of many filmed stage productions: he knows when to give needed space to an ensemble scene and when an exchange or monologue needs tighter framing. He has a discerning eye for the prismatic power of Albee’s tragicomedy and an ear fine-tuned to its mythic rhythms.

by Hadley Hury

Leave a Reply