It’s been a long time.

The bird freewheels through the air, soars above the reed-beds, dives into the marsh hunting frogs, smaller birds, water voles. The wetlands that form an isolated NNR, just outside the tiny village of Stodmarsh. Picturesque rural England pushed to the point of absurdity. It can’t be real, merely an early summer heat haze illusion conjured up for willing eyes that wish these spaces into existence. We could be in Ulverton. The ubiquitous Red Lion waters the phantoms, and on this early morning no human beings are visible in the few dwellings. But we are here, and drive into the car-park. 9.15am and already pounding heat.

A wooden board informs that Augustinian monks were the first to use the land. Flooding the meadows on which they grazed their horses, especially mares in foal. Originally named ‘Stud marsh’.

Into the woods that precede the wetlands. The air is alive with birdsong, every branch singing, avians invisible in the foliage, crying for their mates, marking territory. Reminding us that they exist.

‘Listen to that’ says my father, telescope slung over his right shoulder. ‘A nightingale’. He has years of isolated practise identifying the birdsong. A worthless skill in the modern age.

‘Can you hear the chiffchaff?’

I can.

We hear the machine gun fire of a woodpecker, hidden far in the trees. A brain impact-cushioned by its own tongue. Strange black insects buffet our faces; breathe in too quickly and they’ll clog your lungs, seemingly haphazard frenzies of late spring mating, everything, everywhere alive, breathing.

We are alive. The mind thaws a little, with no pressing need to be anywhere but here, walking across the rickety boardwalk over algaed ponds, onto the marshes.

A wooden sculpture greets us.

HELPING THE BITTERN FIND A HOME

BITTERN:

A thickset heron with all-over bright, pale, buffy-brown plumage covered with dark streaks and bars. It flies on broad, rounded, bowed wings. A secretive bird, very difficult to see, as it moves silently through reeds at water’s edge, looking for fish. The males make a remarkable far-carrying, booming sound in spring. Its dependence on reedbeds and very small population make it a Red List species – one of the most threatened in the UK.

We never see the bittern. Elusive, as one with the reeds. Just comforting to know it is there, surviving as best it can. I look at the sculpture, briefly thinking of the news I saw on early morning TV over tea and toast.

A Tesco riot in Bristol, people starting to become aware of what they are losing, and now willing to fight for it. The sheer absurdity of a Tesco riot is staggering. The banality of everyday life, symbolised by those blue and white lines, erupting into violence. Inevitably, uncannily, the actions mirror the messages Ballard gave us. Suburbs dreaming of violence. The future is boring.

I consider placing an addendum onto a previous piece of writing ‘The Missing Pizza / Every Little Helps’. A Bristol Tesco had been my focus, a fairly standard piece of anti-corporate vitriol; the events in Stokescroft seemed almost too apposite to be coincidence. My partner and I had even idly indulged in fantasies of moving to the place, posters advertising Zion Train and Inner Terrestrials gigs persuading me I could live there (call me shallow).

I could learn to drive, head out to Avalon, take in the West Country and drown myself in Bath Cider. Do the walks mapped in the stupid hippy book I’d bought for a joke, fifty pence in a second-hand store in Whitstable. Now Tesco had taken root there, we figured we may as well stay in London; leave it to the Bristol anarchos to smash the windows.

Onto the marshes proper.

The side ditches and damp reed beds vibrate with the mating cries of the marsh frogs. We look, but they are invisible in the green water, potential food for the harriers that wheel overhead. I saw these birds of prey as a boy, dragged around this place and across the whole United Kingdom, treading foot on all kinds of protected reserves, be it tern colonies in the Farne Islands, crossing the Menai Strait to Ynys Mon, a helicopter ride to the Scilly Isles, or something closer to home, trudging through Blean woods (recently featured in a Guardian supplement), looking for waders at Pegwell Bay, and always trips to Stodmarsh. I realised, so many years later, how much I had to thank and be grateful for, seeing these places, seeing the country I was born into before the JCB’s and hardhats take it forever. Blackwood’s centaur more and more remote.

MARSH HARRIER:

The largest of the harriers, it can be recognised by its long tail and light flight with wings held in a shallow ‘V’. It is distinguishable from other harriers by its larger size, heavier build, broader wings and absence of white on the rump. Females are larger than males and have obvious creamy heads. Its future in the UK is now more secure than at any time during the last century but historical declines and subsequent recovery mean it is an Amber List species.

I stand there, looking at the male marsh harrier, now joined by his female counterpart. I could watch them forever.

On the other side of the path my father has set up his telescope. He smokes a Marlboro Black cigarette, watches the Great Crested Grebe’s perform their mating dance. Massive carp splash in the shallows, spawning.

An elderly couple, fitted in sensible Karrimor footwear, approach. We all exchange greetings, which is in itself a novelty. Only the other day, my flatmate got robbed at broken bottle point for his iPhone, in Stoke Newington. That’s one of the good bits of London, apparently.

The old couple look at the flitting terns through weathered binoculars. I wonder how long they’ve been together, whether it’s still love, how I hope I am doing such things if I ever reach that age, that the bitterns and harriers are still here. I hope the Tesco in Bristol remains smashed and I hope the police are brought to rights for their heavy handed tactics. I hope this is the sign of things changing and I hope I am brave enough to join the fight back.

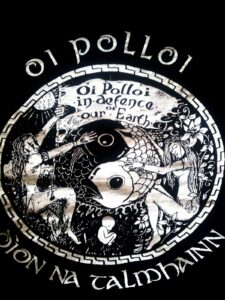

Under my green top I realise I wear the following item

And it all seems to fit. The birds strengthen my resolve, as I stand in a place as yet untouched by the men who want to destroy the land. It belongs to no one, or all by right of birth.

So here we are. A thin green line.

Leave a Reply