Barry Flanagan: Early Works (1965-1982)

Tate Britain, London

From 27th September 2011 to 2nd January 2012

By Paula Barriobero

Even though Barry Flanagan is well known because of his sculptures of hares made during the eighties and the nineties, there was a Barry Flanagan before this one. This is the starting point for this exhibition at Tate Britain which has been conceived with the purpose of discovering the young Flanagan. The exhibition covers from his beginnings as sculptor with Anthony Caro to his participation in the Venice Biennale in 1982 representing United Kingdom. It also includes the creation of the first haresculptures in bronze at the end of the seventies.

The exhibition has been presented in a chronological order through Barry Flanagan’s formative years in Central Saint Martins College of Art and shows how Anthony Caro’s evening lessons changed his vision of sculpture. In these lessons, the sculptor and professor Caro encouraged students to practice sculpture in an experimental way. Students did their independent sculptural practice and then they received critical feedback in a studio crit. Professors took Black Mountain College practices as a model to follow in the artistic teaching.

After graduating in 1966, Flanagan was exposed in two of the greats exhibitions of those years, Op Losse Schroeven curated by Wim Beeren (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam) and When Attitudes Become Form curated by Harald Szeemann (ICA, London) in 1969. These two exhibitions were a landmark in the history of curating exhibitions due to the fact both exhibitions exposed the “new art” of the late 1960s. They brought together arte povera, conceptual, minimal and land art and they questioned those categories and introduced innovative curatorial strategies that would be imitated through the following years.

Encouraged by theoretical texts by Clement Greenberg, students, among them, Flanagan, practiced an urban, abstract form of sculpture using new materials considered not noble, such as ropes, glass or sand. At the same time, there was also an explosion of interest for alchemy and mysterious and Alfred Jarry’s pataphysic and his text, Ubu the King. In fact, Flanagan dedicated a series of sculptures and drawings to this text that can be seen in the exhibition.

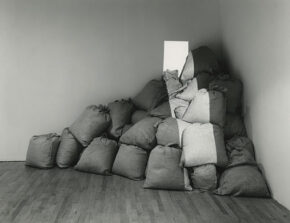

The use of “poor” materials in Flanagan’s sculptures like sand, ropes, wood or cloth is related to the explosion of arte povera in Italy. This movement was theorised by Germano Celant and had protagonists as Mario Merz, Michelangelo Pistoletto or Jannis Kounellis. The arte povera was a reaction against the consumer objects idealized by pop art and the use of noble materials on behalf of minimal.

Flanagan has also been related to land art and with one of their major representatives, Roberth Smithson. In fact, he was shown with artists from povera as well as land art movement in some galleries in Europe and in United States. The use of these particular materials made Flanagan understand sculpture in a particular way because the artist was continually thinking of materials’ properties and the creation process. When he started working with stones, the sense of the play and chance were still present in his work due to the fact that he raised monoliths of stone on very doubtful plinths as in Ubu of Arabia.

The combination of the elements discussed before led the artist to rethink the compromise of him in relation to the art, society and the responsibility of institutions. That’s why he is continually questioning artistic genres such as painting and sculpture, creating new forms of exhibiting works of art and breaking with these fixes and dual notions of the genres. For example in the Tate Britain exhibition there is a cloth fixed on the wall with three wood sticks and a sculpture hanging as if it was a painting.

One of the challenges the curators have had when installing this exhibition has been the fragility of some materials such as sand. Thanks to the notes left by the artist about the way of exhibiting the different pieces, they have been able to install and preserve the works. Once you have seen this exhibition you will realise that even though the artist is well known because of his sculptures from eighties and nineties, there is no doubt that the most interesting works he has made were the ones he made during the sixties and the seventies because of the experimentation with materials and artistic genres.

Leave a Reply