Whenever I think of the place, it’s a grey autumn day in November. Stirrings of Christmas, mist in the air, chill clinging to clothing, those little drops of moisture that would bead my fleece with dew. Old women weighed by plastic bags full of God-knows-what shuffling down the beleaguered high street. The town, back then, had yet to be subjected to the forces of the London-led gentrification that would come to define it in the eyes of the national media.

One of my first memories, of the place and of my life, is of uprooted trees ripped and torn by the hurricane of 1987. My father walked me to playschool, which was cancelled that day, for obvious reasons.

Such a small place, yet as the nineties progressed and the twentieth century sighed its last gasps, style pages enthusiastically featured the old harbour town with increasing regularity. Jarvis Cocker would gush about the place even as the common people got priced out, forced to accept expensive olives and sun-dried tomatoes. Progress, or capitulation. The influx of fashionable Londoners with bulging wallets earned them the sobriquet ‘DFL’s’ and they were met with resistance, even as their money energised the town, made it desirable to the kind of people who wished to make their money in the capital, yet not live there. I still find it hard to decide what I think about such people. I may have become one myself.

Like many other properties in the area, my mother’s house had tripled in value since it had first been purchased in the early 1980s. She was mildly surprised by this but carried on much as she always had. I have hazy images of the old couple who had lived next door, a town run down, hippy residuals, the sea, always the sea, eccentric artists, keening gulls, dunlin and the odd oystercatcher, begrimed men with buckets full of lugworm. Old men from a different reality clutching pints of bitter, dropouts, road protesters. My mother pointing out an ancient Peter Cushing as he cycled round town, our local Van Helsing who in the end could not defeat the vampires.

I spent so long trying to get away from this place. As I get older I find it hard to remember why. My ties to the place are slowly evaporating as my interest in it becomes reinvigorated. My mother will be selling the house due to financial issues, moving to South West Wales to be near family. I have hardly any friends left here.

There was a pub, The Harbour Lights. It overlooked the tidal waters of the Thames Estuary. A biker’s hangout. My mother told me that they dealt drugs there, before I really understood what drugs were. It became the Hotel Continental, an expensive beige edifice that was…pleasant. They sell local beer and ale from the Whitstable Brewery at London prices. I wonder where the bikers went.

How do people disappear?

As a child, I would look at the ugly grey industrial plant that crouched next to the harbour, as it spewed white smoke into the air. I thought the factory made the clouds. The harbour itself became more and more popular, the oysters that attracted so many, and so many articles in the broadsheets a permanent feature, a constant, as eras came and went. Harvested, at least, since Roman times, though the authentic Whitstable oysters were overrun by their Pacific cousins, who of late have been stricken by an outbreak of mollusc herpes, if you can believe it.

I bought a handmade malachite necklace here. It hangs from my partner’s neck to this day. I bought it from one of the craft shops that litter Harbour Street, only grown in popularity as the years march on. I never understood how they could make enough money to keep going. I had taken my mother with me to offer advice. I am no good at shopping.

The cries of the Herring Gulls that nested on our roof would wake me up at five am as the summer sun appeared. The nights so quiet. Now, after years in the capital, whenever I return I lay awake in the pitch black, in the silence, no noise or light pollution. It makes it hard for me to sleep, nowhere for the mind to go but into a shifting past. Dangerous waters to swim in. I can remember seeing road protesters protesting the Thanet Way. I was about eleven years old, but I saw them. I did. I can’t find the information.

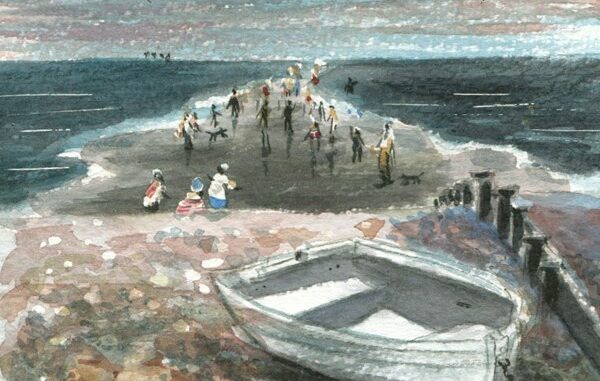

Dangerous waters. The Street. That strange spit of shingle, a literal road to nowhere, jutting three quarters of a mile into Tankerton Bay, submerged and exposed every thirteen hours. Warning signs informing passers by of the danger. Many swimmers have died here, swept away or pulled under by strange currents. Theories abound as to the origins of The Street. As a child, you don’t really question the things that seem commonplace; what else is there to compare them to? I’ve walked out on the thing so many times it seems part of life’s fabric. Visitors to the place, a number of half-forgotten girlfriends who I took there on visits, marvelled at the strangeness of it. They say it’s a natural formation.

Years roll by. I’m dieting on a glut of psychogeography, social history, punk rock, mythology, vegetarian cookbooks, trying to make sense of everything. Turns out there’s a lot of information to digest about this ancient country. A five year long obsession with London starting to settle as I feel more comfortable with the place, where I am. I’m taking root somewhere, elsewhere. The country has been ripping itself apart with a string of protests, police violence, unease everywhere, the city’s topography changing as Occupy sites start springing up everywhere. This movement, it doesn’t come from nowhere, and I’m delving back into Britain’s history for more evidence that there were always people like this, like me, like the people I care about. Some stuff is pretty well documented. Other things, events I can dimly recall hearing and seeing as child, seem to be buried, forgotten recent history. I know more about the Romans than the Thanet Way protesters. But it is there. God bless the internet. I’m Googling, writing down the scraps and shards of information I can glean from old news reports, looking through the deathly-dull news pieces in the Whitstable Times. Find some info on the nineties road protests, and yes, there was one opposing the Thanet Way. I’m not losing my mind, my memory is still holding up. I delve further. Find an interview with a man whose protest name is Fen Lander, he’s written a crazy psychogeographic book entitled The Humanoid Landscape, the British landscape re-imagined as a cherubic being in flight. The book, I discover, is available at The Old Neptune. The Neppy, still one of the most distinct public houses in the country, situated right there on the stony beach, a watering hole featured in the Peter O’Toole film Venus, home to many pissed up nights, drinks with my father where we would look at a portrait of Ian Dury by the artist Ron Chadwick, and now home to this book, a link connecting all my research, my surging feelings that were finding no avenue for articulation, to the place where I grew up. The coincidence I find staggering. I’ve ended up back here, for one last time, before my mother leaves and my reasons for visiting evaporate. It cannot be coincidence.

I don’t live here anymore, but the salt is still in my skin and I can always hear the herring gulls. I can see the rare Hog’s Fennel that lives in abundance on the slopes that lead to the seafront, to the beginning of The Street. The oystercatchers, the dunlin, bladderwrack, mermaid’s purses, dead jellyfish, lugworm tubes, the salt and shingle.

I’m stepping out on that road that leads into the cold, impassive sea, and this time I will find what lies at its end.

Leave a Reply