TRUMBO (dir. Jay Roach, 2015) is an important film because it succeeds in both educating and entertaining. It throws into sharp relief and lends urgent voice to issues in our socio-political landscape today. Set primarily between 1947 and 1960 the film focuses on the Hollywood blacklist and its ramifications for one of filmdom’s most adroit screenwriters. It examines, through a film industry lens, the toxic Red Menace hysteria brewed during the dark and disgraceful days of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. In 21st-Century politics increasingly degraded by right-wing politicians and media outlets using fear and bullying in their strategy to divide and conquer at any cost, the cautionary tale of TRUMBO has a reeking freshness.

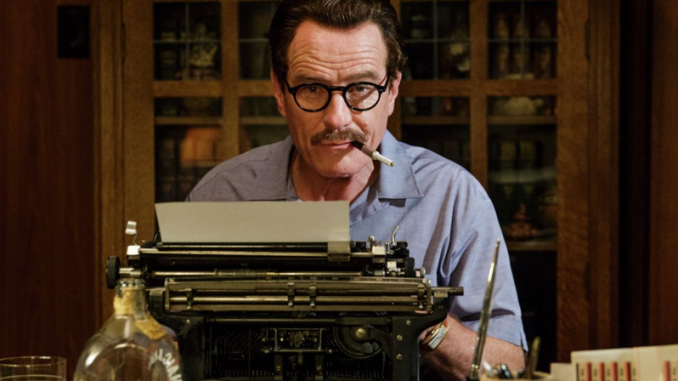

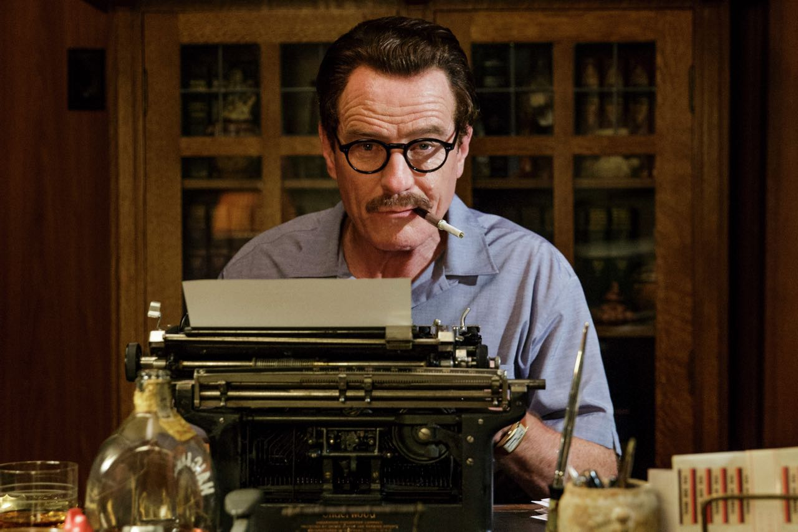

Bryan Cranston, multiple Emmy Award winner for “Breaking Bad”, is superb as Dalton Trumbo, whose scripts for box-office hits like A GUY NAMED JOE and KITTY FOYLE—and later works as diverse as SPARTACUS, THE FIXER, and PAPILLON—placed him in the upper ranks of Hollywood wordsmiths. Like many American artists, intellectuals, and labor leaders, Trumbo became a Communist during the days of Fascism’s ascendancy between the World Wars. Once World War II ended and the Cold War began in earnest, Trumbo and other “sympathizers” were soon targeted by the HUAC. In the perversion of constitutional rights and our body politic that ensued—and which most heinously came to be personified by Sen. Joe McCarthy—even some liberal Democrats like Edward G. Robinson (played convincingly here by Michael Stuhlbarg) are thrown to the zealous demagogues. Some, including Trumbo, are jailed, others crack and willingly give names, and many lose their careers, their families, and a few even their lives. But Trumbo fights to survive, writing scripts pseudonymously. The necessary deception ironically garners him two Academy Awards (for ROMAN HOLIDAY and THE BRAVE ONE), neither of which he could claim.

Jay Roach’s direction, though lacking in verve and cinematic imagination, is respectfully thoughtful. Its deliberateness succeeds in making the story’s most salient points clear, and for an important story that is an asset that needs no apology. Occasional lapses of energy seem more attributable to John McNamara’s workmanlike adaptation of Bruce Cook’s 1977 book Dalton Trumbo. That said, TRUMBO never succumbs to the belabored pomposity of some bio-pics. It has an integrity and inner logic of construction and pace—and some vivid supporting performances—that keep it both watchable and engrossing.

Helen Mirren as Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper is wonderful. It’s another of the film’s assets that many viewers will learn for the first time that Hopper was not merely the sometimes cleverly bitchy troublemaker with the signature hats or, more latterly, a talk-show guest regular who sought to disarm with a feigned scattiness. She held a very influential bully pulpit and, most treacherously in this era, was a vicious red-baiter who wrecked careers and lives. Rather than go for broke, Mirren uses her scenes judiciously to limn this harridan’s bitter, hard-won, calculating knowledge of Hollywood values, her steely, monomaniacal determination for revenge, and the cold, rather exhausted amorality from which to distract she employed the colorful chapeaux, fluty grande-dame voice, and straight-razor smiles. It is a brilliantly considered performance and Mirren executes it with surgical incisiveness.

Cranston’s performance is quietly riveting: his portrayal of Trumbo’s tenacity in adhering to principles never grandstands—it’s pragmatic and worldly-wise—and he evinces the writer’s felicity of language and dry wit more as survival techniques than as a flaunting of epigrams. Diane Lane, as his strong and steadfast wife Cleo, has an almost impassive solidity that works well here. The role gives her little to do but she manages to evoke an essence of bemused patience and common sense that, by all historical accounts, were essential to her own survival as well as that of her husband and family. And the careful progress of the film is enlivened by the hijinks of John Goodman as a low-rent producer for whom Trumbo grinds out schlock during the direst days of his blacklisting, and the canny cameos of Stuhlbarg as Robinson and Dean O’Gorman as Kirk Douglas.

by Hadley Hury

Leave a Reply