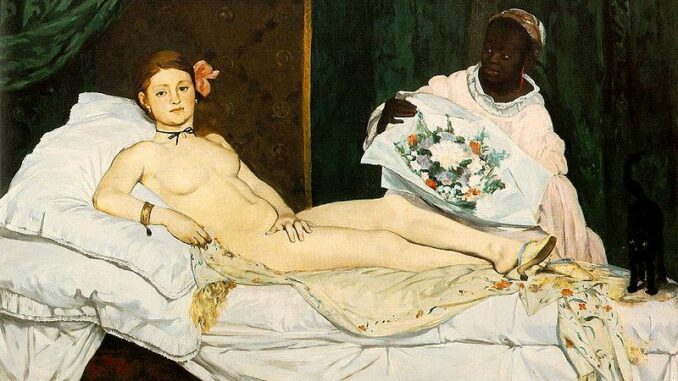

The representation of women in the history of art has been full of assumed constraints, social expectations and political manipulations which toward the end of the 19th century in Paris were shaped by an underlying social current. This was manifested in the production of one of the most notorious representations of women. Manet’s Olympia provoked a reaction caused by a social situation inherent within the masses consciousness and thus the reaction was an outlet for a fear already in existence. This fear was most evident in the salon exhibition of Manet’s Olympia in 1865 which produced critical commentary such as;[1] “a sort of female gorilla, a grotesque” on the painting depicting Victorine Meurent as what has been assumed to be a prostitute. The painting which was rehung higher out of retaliatory reach in the salon was already delayed in exhibition to avoid the scandal of Dejeuner Sur l’herbe. The nude prostitute lies back on the ruffled white pillows of a bed which is assisted in composition by a female black servant holding a bouquet of flowers while a black cat looks out from the bottom of the bed. The fear here not only comes from a;[2] “breached taboo by candidly presenting the image of a prostitute”, a young women in a sexualised profession but symbolizes not only the widespread recognition of prostitution in the 1860s bourgeoisie society but their paranoia about the growth of the working classes.

In the 1860s the redesign of Paris deliberately destroyed the working class areas with their brothels in order to control the population with wide boulevards and conventional moral codes. The brothels were displaced by high rents and replaced by larger, richer maisons de tolerance while smaller garnis survived thanks to prostitution being allowed to be practiced without penalty in 1866. Prostitutes suddenly became more visible on the streets of Paris and so;[3] “Olympia, contemporary heroine that she is” represents the image of modern women. Manet’s sharp aesthetic break away from a traditional representation of women such as Venus reveals a highly personalized nude, rigid;[4] “who conveys instead a spirit of modern Parisian intelligence”

Prostitution as a symbol of lower class society is undermined by upcoming prostitutes constituting “a class”. Prostitution was like a business with the internationalisation of commodity and clientele and a cultivation of regular customers who allowed prostitutes or grisettes to learn and manage their value as market commodities to;[5] “have infiltrated business affairs to such an extent that the French economy could not function without the funds in circulation through sexual commerce”. In some cases prostitutes were setting fashion trends as well as emulating “proper ladies”.

This conflict between middle and working classes in Paris provided a slice of the shock reaction which held a resonance of the revolution, but what was more universally felt was Olympia’s overtly, unapologetic acceptance of her own sexuality. This woman is represented as being completely in control of her overtly suggested sexuality with her powerfully confident pose and confrontational gaze which must certainly prefigure women’s liberation as an equal. Olympia’s sexuality is depicted symbolically with the black cat reflecting the slang equivalent of female sexual genitalia, the tropical exoticism of the flowers, the harem evocation of the black servant, the hand of Olympia self-consciously covering her pubic area and her overall nakedness.[6] “To Manet the prostitute of his own day recalled a divine prototype” of the classic Venus pudica position as used from Titian’s Venus of Urbino, 1538, on the ambiguous Olympia, who’s modelled appearance stands out from the flat background evoking a tradition of contemporary pornographic photographs of lower class prostitutes rather than the submissive Venus. Victorine Meurant, Manet’s favourite model who often posed for such photographs as well as appearing in eight of Manet’s works. She herself was a painter as well as a model and often condemned by contemporary writers for being promiscuous and alcoholic. Meurent took the typically masculine persona of artist while maintaining the typically feminine role of object. This involvement of roles introduced contemporary women into modernity which was interpreted as a challenge to male dominance. This has been seen as evident in Olympia’s gaze which counters the male gaze on traditional submissive Venus representations of women but also represents a;[7] “self-protective wariness of the prostitute” as well as her individualized, non-conforming to traditional notions of women which may explain critical descriptions of Olympia’s cold, masculinized androgyny.

The highly polished and finished style of Olympia has no half-tones so the transition from model to background is bold and harsh. The flat, two dimensional background in contrast to the modelled Olympia shows how the whole picture revolves around accentuating the central figure and pushing her into public space of thought.

Gotta love the dangling of the slipper!