I was an Advanced Dungeons & Dragons kid, you know, all the fantasy stuff that stimulated the creative mind that was actually about telling interesting stories with positive outcomes. Ben Croshaw of The Escapist Magazine

Years ago, on one of my many ventures into the High Museum of Art, I saw a sculpture in a room of the Modern Art wing. This sculpture was a few strips of insulation padding attached to the upper portion of the room’s wall. This extended down the wall and a foot or so onto the floor. To many patrons whose interest was centered on the classical works present on the floors below this may have seemed like rubbish tacked onto a wall – and in a utilitarian sense that was quite right. However the artist’s intent in this sculpture was to allow his art to share a plane of existence with us; that is, it literally left the plane of the wall and entered the one we used: the floor.

One cannot say such intent is often seen in works of static, visual art, and while it is unique in that overly specific sense, this intent has appeared before in other work.

The official year of release of Gary Gygax’s Dungeons & Dragons is 1974. Although over the subsequent decades it has undergone many changes, its modern form is still a powerful example of interactive art. For is literature not an art? Is painting not an art? Is the human mind itself not a true work of art in its endless source of inspiration and emotion?

The stories one plays through in a game of Dungeons & Dragons are like any stories one reads for leisure: they have protagonists and antagonists, trials and tribulations, tests of wit and strength. The obvious difference between classic, monomythical literature and Dungeons & Dragons is the level at which one interacts with them. When you read a book, you turn the pages at your own pace. You can reread passages at will and choose when to stop reading. However, the characters before the reader act on their own accord with the reader simply observing the life of a person without any input. The reader can make no change, save for tearing pages from the book itself.

In a play the players add emotion to their respective parts, designers create the costumes and stage managers choose what the scenery will look like. Makeup artists, sound and lighting technicians all apply their own effects, yet it is the original playwright who controls what the characters say, where they go, what actions they perform and when.

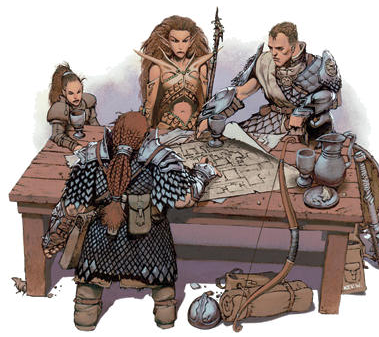

Though there is a writer behind every scenario in Dungeons & Dragons, they create a much broader realm. They do not make the characters, choose what they say, decide where they go, dictate who they kill, or when they sleep. Almost the entirety of the game is in the hands of those playing it. Even the scenery in the earlier editions of the game is created in the mind of the players and the results of many actions are left to chance. The writer writes a world and nothing more: the player makes the world their home; somewhere they live and breathe and act on their own will, not somewhere in which they observe others living.

I once read a Dungeons & Dragons scenario in which a quest is offered to the playing party, and while accepting it sends them off into a world of battles and trials, they could just as easily deny it and do something else. Often the writer plans for this to happen and creates alternate quests. That is a great difference in itself: a book’s story is written with the reader hardly in mind, but a game of Dungeons & Dragons is written solely for the reader to come and be in it, not to watch from afar. The writing of such things is far more personal than that which is read in books or seen in plays or on TV. A game show does not care if you are a history buff or not, it will ask you historical questions regardless. But if something in D&D does not suit you, just find another path. Better yet, be human and speak to humans: if you must solve a riddle to open a door but have feeble intellect, surely your party’s wizard is wise enough to answer. D&D does not create a world for one to walk about in and indulge in on one’s own, it creates worlds for groups of people to share together.

While the game itself is sadly easy to dismiss as the product of boredom or as a way to pass time – even as a Satanic ritual by some – you often only hear such things from those who prefer to sit away and hide behind the veil of the fourth wall. That is not to say they are frightened, only that their preferences differ. The most important aspect of any human creation is its humanity. For if we give no human purpose to our creations, what purpose does it hold for us?

In any real work of art, one can see the humanity in it, and it is very easy to see the delicate work of a human behind worlds that are created for humans. We use ourselves for ourselves: work makes results we can feel and use.

Leave a Reply