Rather naively and perhaps more foolishly, my initial impressions of Red Light Winter were one of romance and warmth, the red light of the winter glowing, a semiotic of fun, frolics and passion, amongst the bitterness of the cold. I must have bypassed Amsterdam written in the Bath Theatre programme and the picture of a redly lit woman in her underwear standing in a window, my innocent head clearly concentrating on the words ‘rekindle their friendship’ with ‘romance’ and ‘love triangle’.

I don’t mean to put all my focus on the two sexual acts that occurred throughout the play and risk myself sounding like a prude or not appreciative of these choices, but these are the two events that stuck out to me loud and clear and in my head on the way home and the next morning.

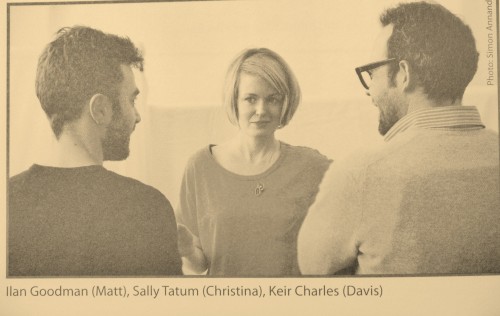

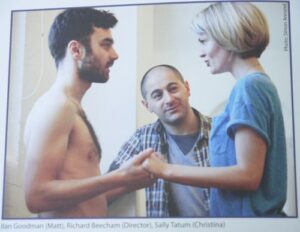

In the first act, Christina (Sally Tatum) takes off her clothes, walks towards Matt (Ilan Goodman) and confidently strips him of his. This reminded me that Matt’s character trait was ‘being led’ and prompted me of his purity; he had not had sex in three and a half years. It was tender and evocative. However, this moment would have been more effective if the lights proceeded to go down, to end the scene and not continue it.

The silence had already spoken, but the act of the sex and the clear enjoyment from Matt disrupted this vulnerable and precious occurrence. Equally the audience knew what was to occur, it had been talked about for a while now, described to us through Davis (Kier Charles) appreciation of the female ‘apparatus’.

Again, the simulation of sex, or rather Davis getting his kicks from Christina, in act two, became excessive. Davis is brutally attacking Christina with demeaning and misogynistic insults before this. These vile words were enough to inflict him with a repugnant status and reach me emotionally in wanting to care for Christina, feeling the pain of the words myself.

However the endurance of getting this message across through this visually intense physical act took away the impact of those words. It somewhat numbed my loathing for Davis and guiltily, decreased my sympathies for Christina because she did not stop him.

I understand that the sadness lay in Christina’s wish for Davis to love her (which she acquired through sex or love making as she called it), but it was hard to feel sympathetic and fully understand because her character was not explored. The real pain would have been collected from a further exploration of her life, gathered by the answering of vital questions. What was her need for putting on a French accent and for lying about her place of birth? Why was she a prostitute? Why did she marry a man, knowing he was gay? Without these answers, she was a stranger and it just became too hard to connect.

In the second act, I felt like there might be a break through. Christina reveals that she has Aids; the revelation of this is truly heart-breaking, though the real crux of the sadness and pivotal moment is when she confides in Matt. It seemed her walls were falling down and the repercussions of her life were going to be explained. However, this sadly failed to launch.

In the second act, I felt like there might be a break through. Christina reveals that she has Aids; the revelation of this is truly heart-breaking, though the real crux of the sadness and pivotal moment is when she confides in Matt. It seemed her walls were falling down and the repercussions of her life were going to be explained. However, this sadly failed to launch.

In the version that Rapp presented, I wished for Christina and Matt to be together. She felt like a blessing in (literal and metaphorical) disguise, come to rescue him after his three and a half year heartbreak and him her, as a gentleman and a one woman man, his priorities on an emotional rather than physical level. However, I understand the premise that life is not as simple as fitting into this perfect ideology – cue unrequited love, for it is this which Rapp is exploring.

If only Rapp favoured time exploring the character’s background and what had by passed each individual to determine them each a wreck in their own way. So many things were unanswered that I found it hard to have much feeling for all the characters in the end. I enjoyed act one a lot more because things started to unravel, such as Matts sudden fit of uncontrollable weeping, for good reason – a heart wrenching discovery informs us. His meek and lovable character suggests that his tears are over a lost love. However in the second act, the same state of hysteria and obsessive pining towards Christina loses the clarity I thought I had.

The sign that Davis could be showing remorse at the end when he asks Christina if he had hurt her and walks out deeming himself not a good person, seemed an attempt to show that underneath there is some psychological problem, a person covering his hurt through afflicting pain onto others. Yet this does not get explored and it instead makes his character murky.

However, reading the programme and confusing further, it seems that Rapp’s intention was not to make Davis’s history an influential part, Davis’ wicked behaviour rather a cover up or denial, from his falling in love with Christina, in order to preserve his friendship with Matt. Unfortunately, the stealing of Matt’s girlfriend and engagement to her makes the case for Davis wanting friendship rather weak. Equally, there is partial evidence for Davis loving Christina, as she describes how they talked all through the night and is convinced they love each other, but Davis’ vulgar mistreatment is just too strong to naturally derive this concept.

Reading on from this revelation, Rapp’s premise is extremely interesting. He writes how ‘the gray areas’ intrigued him, ‘how we hold on to the tiniest details when we encounter someone we’re bewitched by, and how the other person might not remember the most obvious things from that meeting; the cruelty and pain of being disremembered versus the alchemy of selective memory and how we twist and distort it to rationalize and justify what we want to believe about the object of our affection; how we misinterpret minutiae and mythologize the most insignificant looks and lilts of the voice; how the most meaningless actions can carry enormous, existentially romantic impact’.

These ideas are truly fascinating, due to the fact that they are so accurate of the human psyche. Some of these details showed, but unfortunately the concept became hazed. I did not see any of these criteria affecting Davis.

The acting is brilliant. Red Light Winter could be brilliant. If only words had spoken more than the actions. If only history was provided and if only a clear concept was decided upon.

Couldn’t agree more Lauren. Rapp’s ideas and intentions, and the actual piece on stage didn’t seem to correlate. Some superbly layered performances but a lack of richness and clarity in the script unfortunately left me slightly disappointed.

Thank you for your comment Adam, I really appreciate it, especially that you too felt the same. I felt that maybe I was missing a trick and not understanding the real meaning of the play – but I figure you shouldn’t have to look at a programme to understand what something is about.

Will be really interesting to see the film.

I didn’t know there was a film in the making – just looked it up! Will be very interested to see it, if only to observe how it translates to the screen and if they adapt the playtext in any way.