Campaigners for a major Schiele exhibition in England can put away their placards. There hasn’t been a museum exhibition of his work here for over twenty years, but until 18 January 2015 Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude is on display at the Courtauld Gallery. Part of the gallery’s exploration of the major themes in drawing, the show concentrates on his unflinching portrayal of the human figure. Usually the female nude, though there are also examples of his own angular, painfully elongated self-portraits and occasional other male models.

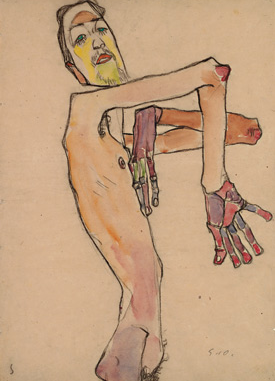

Egon Schiele (1890-1918)

Erwin Dominik Osen, Nude with Crossed Arms, 1910

Black chalk, watercolour and gouache

44.7 x 31.5 cm

The Leopold Museum, Vienna

Schiele came to prominence during his short life (1890-1918) and had collectors and museums buying his work whilst he was alive. At the time Gustav Klimt was the central figure in the Viennese art world and after Schiele became disillusioned with the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts Klimt became Schiele’s mentor. His drawing was so disliked by the establishment that when Schiele dropped out of art school his teacher begged him not to tell anyone that he had taught him.

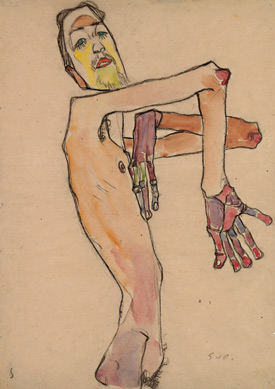

The flat first image in the show – a crouched body from 1909 owes a debt to Klimt. But somehow before the next image from 1910 Schiele has found his own language, suddenly able to express his own experiences and feelings in a new, dynamic way. There is no obvious progression, Schiele’s painful, emaciated new style suddenly appears. Sickly green washes, he even opens up the flesh to see the vertebrae in parts of the neck. All was not well in the Schiele mind.

He had had a childhood full of death. A sister lost, a mother miscarrying many times, a father going mad and dying. His relationship with his sister Gertrude was, to put it politely, unusual. She was four years younger, regularly posed for him nude and at one point they went off together to Trieste and relived their parent’s honeymoon. Quite how accurately is unknown.

In a further problematical series of images Schiele was given permission by a Viennese gynaecologist to visit the maternity wards and sketch mothers and children. Disconcerting and wouldn’t-have-been-allowed-today it resulted in some Mother and Child images that completely subvert that typical artistic trope.

The images all contain the body and nothing but the body. There is no context, no help in reading a narrative. Schiele has completely dropped the pretence that nudes had to masquerade as nymphs and Greek Goddesses to be acceptable subjects for art. His keen eye is searching out every twist, sag and sinew in the human body.

But he breaks the drawing-from-life rule that gives his line its elegant economy. His colour palette includes a nipple pink which he reaches for every time he paints a nipple. His method was to draw from life, without correction, but only at the start of the process of creation. He would then put the image aside and return to it later, without the model in front of him for a spot of colouring-in. It is here that his demons really come to the fore. His greys and greens suggest living corpses. Now the unnerving aspect of his work is complete. The early images in the show that are painted in realistic tones attract. The later ones disturb with their multi-muted colouring and scratches of green.

The show at the Courtauld brings together images of the human body that still seem radical today. They show his virtuosity and uncompromising scrutiny of his models and himself. With Schiele exhibitions being so rare in the UK, this show is recommended.

Leave a Reply