Twenty-three years after its release this film can still lay claim to one of the most rhapsodic opening sequences in film history. To the sweeping, passionate overture of Patrick Doyle’s score, Don Pedro and his men charge homeward from the wars on their steeds across the fields of Tuscany. As they arrive at Leonato’s villa, they splash through the fountains in progressive states of undress to wash away the dust while the gleeful women, dressed all in summer white, watch and laugh with unconstrained delight.

“Man is a giddy thing”, observes Benedick near the benedictory ending of Shakespeare’s play, and the bemused smile on the face of Kenneth Branagh, who directs and stars in this excellent adaptation, perfectly evokes the spirit of the playwright’s answer to the human predicament: there is nothing for it but to love. For 111 rapturous minutes that is what we see on the screen and what draws us into its emotionally charged bear-hug embrace—love. This Much Ado About Nothing is both faithful to the text and great-hearted. The film is a sumptuous visual feast. There are the hills of northern Italy with their upland Mediterranean greenery, the undulating geometries of burnished vineyards, a paradisical villa, robin’s-egg-blue skies, and blooming myrtle, laurel and geraniums everywhere. In Branagh’s hands the text comes to life with vibrating intelligence and palpable energy.

Throughout the film the characters, sun-bronzed and sensuous in white cotton and soft leather, frequently touch one another. The fond feeling and physical expression are not reserved for the story’s leads and lovers; everyone touches—young, old, servants, princes, friends. As he has proven both on stage and in film Branagh is a shrewd purveyor of Shakespeare, and here there is an emotional warmth that gives full dimension to the play and which is too often missing. Man is, indeed, a giddy thing, and every day brings fresh news and ancient reminders of our capacities for goodness, brutality, spirit, and ignorance. This production of Much Ado doesn’t avoid the shadows of Shakespeare’s play but it doesn’t dwell there—the director embraces the work’s greater potential, that of satisfying our occasional need for a bit of unadulterated joy.

Keeping the two parallel plot lines moving with deft speed, Branagh also succeeds in making much of the play clearer than do many theatre productions. The film focuses our attention not merely on the verbal sparring of Benedick and Beatrice (Emma Thompson) as their mutual antagonism finds itself ambushed by love, but on love’s essential power to find a way, to make good, to put things right. Much Ado affirms that few of us are worthy of love—we abuse it, and yet somehow, in spite of us it survives. Shakespeare is writing here of young love, cautious love, trust vs. treachery, eros and agape, mistaken identity and misprised honor. The film evinces that essence. It reveals our feeble efforts at getting at the truth of one another and the horrible waste that can attend our failure. Rarely have the converging story lines of Beatrice and Benedick, and the younger lovers, Hero (Kate Beckinsale) and Claudio (Robert Sean Leonard) been balanced so effectively. Like Austen’s couples two hundred years later in Pride and Prejudice—another eidetic work of art concerned with realities and appearances and the perils of social mediation—Branagh’s and Thompson’s worldly-wise characters must cut through society’s, and their own, misperceptions about who each genuinely is before they can discover their love, while the first-timers come even more tragically close to missing the truth.

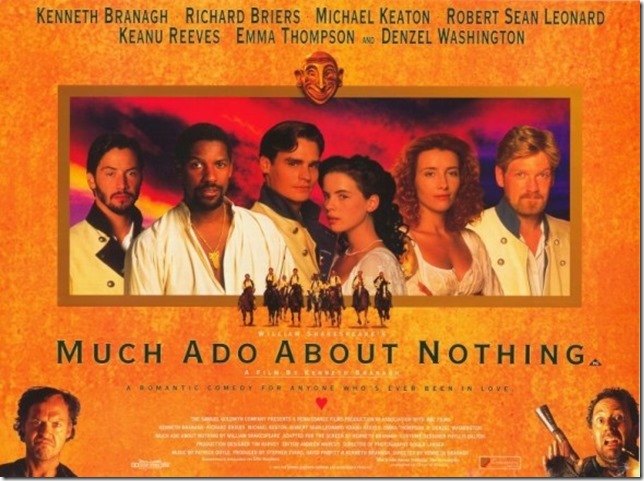

Thompson’s Beatrice embodies the production’s intelligence, exuberance, and warmth. Often actors sacrifice Beatrice’s “merriness” of heart to her quick tongue. As she has shown over and again, Thompson can give us a strong woman’s complexity, a capacity for wise feeling. In her Beatrice we can believe equally the seriousness of purpose, the wry wit, and the fact that when she was born “there was a star danced”. The supporting cast is good, and helpfully attractive. Only Keanu Reeves is not quite up to par; his performance as Don Juan is monotonic. Although his dark good looks work, and though admittedly his is the piece’s thankless role, he manages little with Don Juan’s misanthropic melancholy except a sneer. Denzel Washington’s Don Pedro and Leonard’s Claudio, as well as the Leonato of Richard Briers and Phyllida Law’s luminous Ursula, reflect the glow of the director’s vision. Michael Keaton does a highly stylized turn as the local constable Dogberry. It’s a surreal, outsized performance, outrageous but efficient—limning unforgettably everyone’s worst idea of any official entrusted with the law who is egotistical, deluded, and stupid.

Roger Lanser’s cinematography is exquisite, framing important speeches and exposition in close-up and enhancing lyrical passages with an appropriate dance-like fluidity. Doyle’s score is by turns thrilling, tender, lush, impassioned—it’s the breath of this film and never less than inspired and inspiring.

by Hadley Hury

Leave a Reply