After an interesting lecture on bones at the Wallace Collection my eye was drawn to another bone-based lunch-time talk, this time at the Grant Museum of Zoology. I have given bones little thought since I broke my wrist years ago, so its good to know that there are people devoting their lives to these indispensable parts of human and animal bodies.

Ben Garrod is a PhD student, researching primate evolution and morphometrics. I didn’t know what that was either, so here’s a link to a definition. I then had to look up taxonomic, which told me it was Of or relating to taxonomy. I could have told them that, so I had to look up taxonomy, and eventually discovered it was of course, The classification of organisms in an ordered system that indicates natural relationships.

Ben Garrod explaining something to someone

Garrod is a primatologist and has worked with primates around the world for years. He is especially interested in the monkeys of the Caribbean, who descend from African monkeys but have developed in different ways. Have they speciated? That’s hard to say as no one is sure of the definition of a new species. Am I glad that I have learned the word speciated? Yes. Am I finding it difficult to work speciated into everyday conversations? Yes. If you can suggest a sentence containing speciated that I could use at the pub then please do tell.

Owing to his obsession with bones, Garrod is known as the Bone Man. If that sounds like a persona that would transfer naturally to TV, you’re behind the curve. Garrod has already shot a series for BBC4 that will be shown in January 2014. He’s an enthusiatic presenter and I think the show will be worth staying in for, although to make a definitive call I’d obviously need to know what you were thinking of going out to see instead.

The Grant Museum has over 60,000 specimens, and Garrod was allowed to choose one object to discuss. In the end he couldn’t limit himself to one bone, but he did limit himself to one animal.

‘Does anyone know what this is?’ he asked the audience, holding up what looked like a club.

It looked so much like a club that it couldn’t be a club.

‘A club?’ asked someone on the front row.

‘No, not a club.’

A few more guesses and we were out of ideas.

‘It’s a walrus’s baculum,’ Garrod announced.

At that stage I would have had to look up baculum, but luckily Garrod knew his audience and added, ‘A walrus’s penis bone.’ He passed it round for every one to handle. I would say its surprisingly heavy, but I’m not sure why I am surprised. I have nothing to compare it to. Maybe its surprisingly light.

The baculum did the rounds of the room and Garrod lifted up the large walrus skull on the table next to him. He had chosen the Giant Walrus to tell us about, describing their skulls as sexy. He explained that although they had enormous teeth, they did not use them for fighting or scavenging for food. All they use them for is getting out of the sea. They use their flat teeth to create a vacuum in their mouths which helps with their industrial processing of clams and mussels. In 15 minutes a Giant Walrus has been known to eat over 5000 clams, without getting any shell in its stomach.

Contrary to what you might think if you have seen the Horniman museum’s stuffed walrus, Giant Walruses are not that big. The Victorian taxidermist had never seen a real walrus and just stuffed the skin until it was full. But a real walrus doesn’t fill its skin – like a Shar Pei dog they have huge folds all over their bodies.

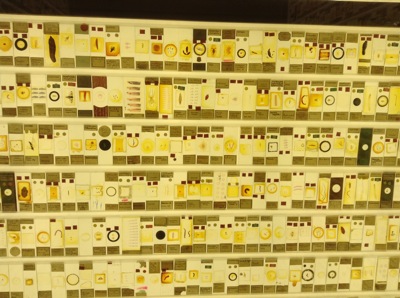

Even if there is no special talk there are plenty of fascinating specimens on show at the museum, including the Micrarium, a small part of which is pictured above. It’s located on University Street, London, WC1 and is open Monday to Saturday 1pm – 5pm.

Leave a Reply